November 07, 2013

Pride, professionals and a man named ‘Pooch’

The story behind the lost years of the Andover-Exeter rivalryby Amy Morris

The hooligans who applied a fresh coat of red paint to the main hall of Exeter’s academic building didn’t miss a spot. Everything, including the floor, gleamed crimson. The 1893 caper came in the wake of the school’s 26-10 victory over Andover on its home gridiron, a victory that was made sweeter by four years of mounting vitriol between the archrivals.

The Boston Globe reported that the school believed outsiders were to blame for all the red paint, and noted the befuddlement of one student in particular, the school’s star halfback, who “looked somewhat pleased as he everywhere saw ‘Donny’ written in Crimson.”

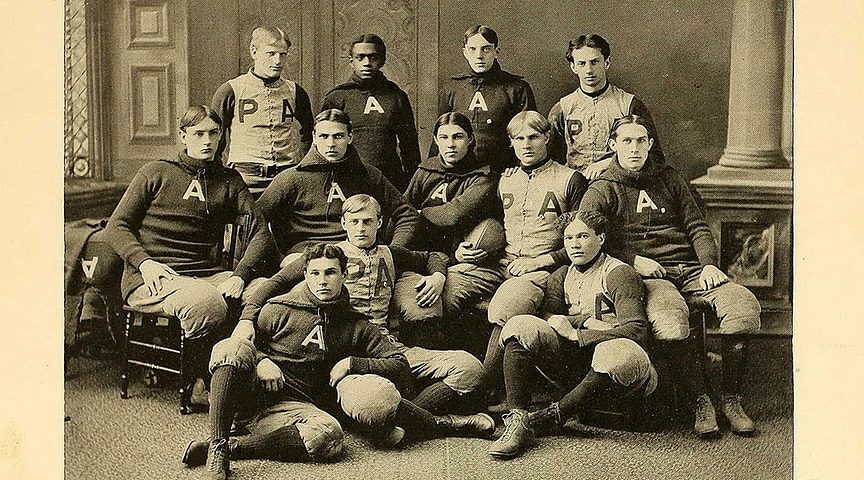

William F. Donovan had delivered Exeter’s November 11 victory before a crowd of five thousand fans. His performance that day was so superb that even the Phillipian praised him. Donovan, it reported, “played by far the best game for Exeter,” doing “most of her running and every time he started he made a gain.” The reporter ruminated that Exeter’s star halfback “must have had wonderful training before he went there.”

Little did the Phillipian reporter know that the same halfback would soon be at the center of a controversy that would lead to a three-year break in the Andover-Exeter rivalry and help start a national conversation about the use of professional athletes, or ringers, in school sports.

The turn of events came, when, days later, the Boston Herald revealed that Donovan and two other teammates had enrolled in Exeter late that fall, and that all three had left campus for good soon after the game. Exeter, it seemed, had brought in ringers.

“Donny” was none other than “Pooch” Donovan, a well-known athlete who had performed in man-versus-horse shows for the Barnum and Bailey Circus and competed locally in hook-and-ladder competitions. Just prior to his stint at Exeter, “Pooch” was coaching track at Worcester Academy. The Worcester Daily Spy reported that “Pooch’s” friends thought it “a little peculiar, to say the least, that a man of his age should enter [a] preparatory [school].” (He was 27.)

The football rivalry, which began in 1878, had suffered a major setback. But charges that ringers had participated in games between the two schools were nothing new. In 1889, Andover’s second baseman, Jim White, defected to Exeter, and then pitched the Red to a 3-2 win over Blue. After the game, while the Andover nine waited on the platform of the Exeter train station, Exeter’s team paraded by with White hoisted on their shoulders. A near riot ensued, leaving one person unconscious, and delivering a head injury to another: Andover’s acting principal, Edward Coy.

Upon his return to Andover, Coy wrote to Exeter Principal Walter Scott, decrying White’s hasty admission to the school and to its baseball team and insinuating that the pitcher had been paid by someone at Exeter, and therefore was ineligible to play. Coy then noted that “the exhibition of rowdyism and violence to which we were all exposed last Saturday has brought matters to a crisis,” and decreed that “athletic contests between Phillips Academy and the Phillips Exeter Academy are at an end.”

On the matter of paying its athletes – or at least Jim White – Andover’s hands may not have been entirely clean. In “The Story of Phillips Exeter,” Myron R. Williams relayed a story from a member of Exeter’s Class of 1892:

Andover, it seems, had a player named Jim White, who was paid a salary of $200. Two Exeter brothers succeeded in inducing him to transfer to Exeter for a $100 raise.

As a result of the 1889 incident, the archrivals cancelled the football game the following November. In May of 1890, the two schools negotiated the “Rules for the Government of Athletic Contests,” which forbade the use of professional athletes by either school. But because both of Exeter’s pitchers in 1890 has been paid, at some point or another, in their career (Jim White was one of them), the baseball game that spring was also cancelled.

The games soon resumed, but suspicions of “professionalism” on both sides continued. Meanwhile, the debate on the issue, especially in football, went national. Harvard President Charles Eliot led the charge, calling for its abolition. With players wearing little to no protective head or neck gear, injuries, even some fatal, were mounting. But so, too, was the sport’s popularity.

A rivalry shattered

The final break between Andover and Exeter occurred after the revelations about “Pooch” Donovan. The Andover student body unanimously voted to suspend all future competitions with Exeter. The front page of the Boston Journal on November 27, 1893 screamed “A BOMBSHELL! Phillips Andover and Phillips Exeter in Conflict.” Exeter students responded to Andover’s decision in the next day’s Boston Globe. Beneath the headline “Exeter is Amused,” the Globe reported that the consensus on the New Hampshire campus was that Andover had known all about Donovan, and was acting like “cry baby.”

The Harvard Crimson then chimed in, claiming that Andover’s quarterback, John Glynn, was a “professional pugilist,” and that Andover’s claim of ignorance about Donovan was “far-fetched,” since “each school endorsed its rival's eleven some days before the game.”

That December Teddy Roosevelt, a graduate of Groton who would soon become New York City’s police commissioner, weighed in on the controversy in Harpers Weekly. “If it be true that one of the Exeter team of schoolboys has played this year with three professionals, grown men, admitted in the school for sole purpose of playing football, then this team and academy should be cut off from all athletic intercourse,” he declared.

On February 28, 1894, 180 Andover alumni gathered at the Hotel Vendome in Boston for the fifth annual alumni dinner. The evening became a protest rally against professionalism in school sports, with the event’s keynote speakers—Massachusetts Governor Frederic Greenbalge, Harvard’s Charles Eliot and Andover Principal Cecil Bancroft—all inveighing against it. After a previous speaker called Andover and Exeter “twin roses on one stem,” Greenbalge declared, “Let the rivalry between the ‘roses’ be carried on in high, chivalric plane!”

He then called upon the students in the audience to make sure that in future contests, “chivalry and manliness and gentleness” are “always triumphant. In that way, you will be exercising a salutary influence on the whole body of people.” The Governor’s charge was met with loud applause. Bancroft spoke next, reassuring all present that all members of the Andover eleven were fully enrolled, “or were when I left this morning.” The quip stirred laughter throughout the full house.

Then Eliot stated his conviction that athletics were “an end,” and that of them all, it was gymnastics that most contributed “to the soundness of mind.” The Boston Journal noted, that unlike the previous speakers, “these observations were not met with tumultuous applause.”

Repairing the relationship

Andover and Exeter would not meet on the playing field again until 1896. During that time, Lawrenceville improbably became Andover’s chief rival. The contests became drudgery, with teams having to travel between Massachusetts and New Jersey, with few fans accompanying them. Enthusiasm for athletics at both “Phillipses” nosedived, prompting the Ivies to take notice. Two of their most important athletic feeders risked running dry.

The Yale Daily News wrote in November of 1894 that the “failure of Andover and Exeter to meet in football this year may mean the end of a custom which has proven extremely beneficial to the athletic interests of both Yale and Harvard.” A year later, the Crimson joined the call for reconciliation. The Andover-Exeter games were “rivaled in interest only by the corresponding events between Harvard and Yale,” it said; reviving them “should obtain the heartiest support of all true friends of athletics.”

By 1896, Andover had softened its position. When Exeter’s new principal, Harlan Amen, wrote Bancroft in June to say that the school was determined “to have clean athletics.” Bancroft replied that he’d be willing to help resolve the matter as long as no alumni or other outside parties were involved. In October, the two agreed to announce the reconciliation in separate all-school chapel meetings.

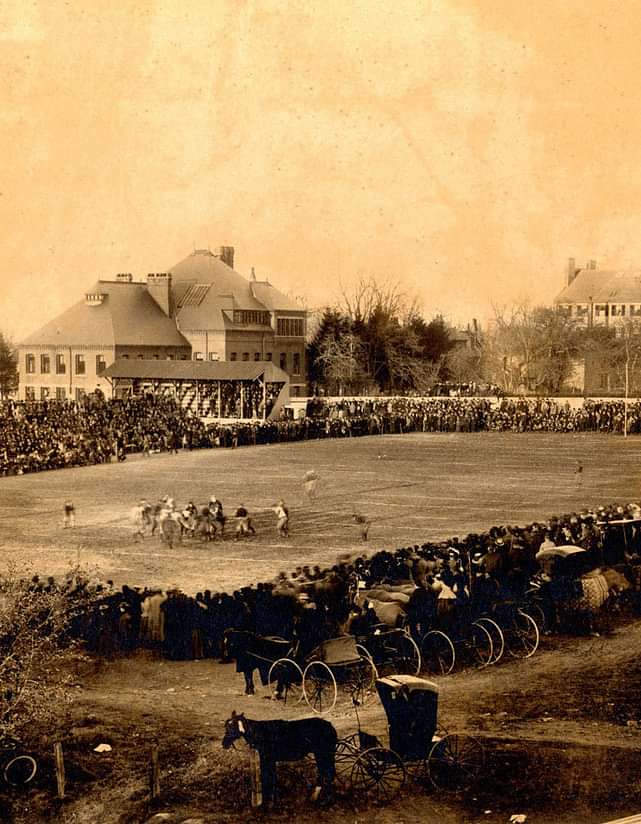

On November 7, the Andover Athletic Advisory Committee passed a resolution to renew the contests. The Phillipian praised the move, saying “the athletic welfare of both schools demanded it. Natural rivals could not afford such an unnatural condition of affairs for too long a time.” A week later, Andover and Exeter resumed play, meeting on the Andover gridiron before a crowd of thousands. Andover won, 28-0.

An editorial in Andover's student literary magazine, the Mirror, circulated only after the reunion game had been played—admitted that the 1893 scandal was perhaps more nuanced than Andover had previously claimed. Titled “Shall We Play Exeter?” the piece noted that “the situation was understood clearly beforehand, and instead of being ignorant that she was to meet professionals, Andover rather sought glory in the hope of defeating them, whether or no.”

As for “Pooch” Donovan, he went on to play for other schools that season, and joined Harvard as an athletic trainer in 1906, where he remained for twenty years. Upon his death in 1928, the New York Times noted how his work with five college generations at Harvard “led him to international recognition as a coach and trainer of athletes.” The story also mentioned his brief time at Exeter, explaining,

Pooch was also a football player of considerable ability. Eligibility rules were not as strict in those days as now, and Pooch once had the unusual experience of playing for a preparatory school one Saturday and a college the following week. He played for Exeter, scoring 25 points against Andover, and the following Saturday he starred with Georgetown.