October 06, 2020

A soul coming into itself

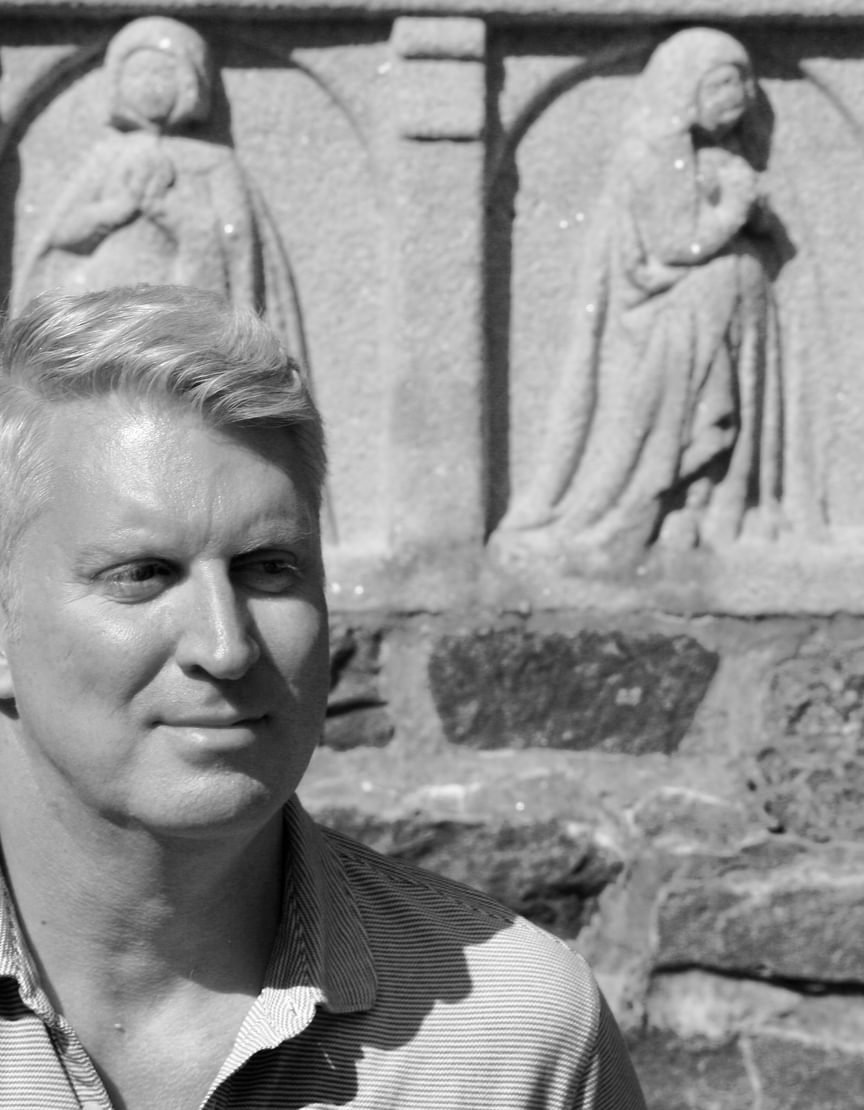

Kirkland Hamill ’86’s new book reflects on his tumultuous childhoodby Caroline Langston Jarboe ’86

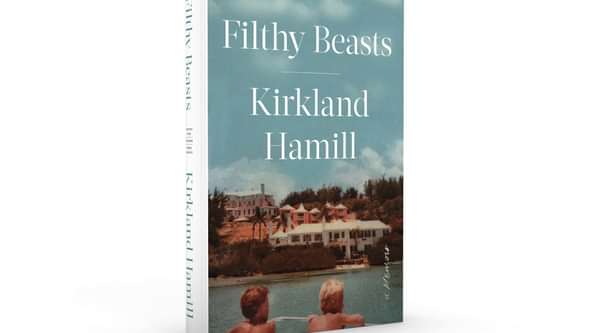

Kirkland Hamill ’86’s voice was brimming with enthusiasm when I caught up with him on the phone in July, fresh off receiving the fantastic New York Times review of his memoir, Filthy Beasts. “His Mother Was Neglectful, Drunk, and Absolutely Riveting to Him” read the headline. But the excitement in his voice had less to do with reaching the apex of literary recognition than with the joy that, finally, he was the author of his own story—and that audiences were eager to listen.

“It’s hitting pretty big in Bermuda!” he said referring to the island home where he’d spent much of his childhood, and the backdrop for some of the book’s most troubling scenes of his mother’s decline and his adolescent confusion.

The book’s success is a confirmation long in coming. The second of three sons, Hamill had spent decades trying to live within his family’s cloud of competing narratives and the book is Hamill’s testament to disentangling them: He recounts his childhood in the lush atmosphere of his father’s wealthy New York family, in which his young, beautiful mother—a middle-class Bermuda native—always felt like an interloper. In an environment circumscribed by the rituals of sport, alcohol, casual racism, and clubby sociability, Hamill is conscious of being unlike either of his rough-and-tumble brothers. He feels ungainly and uncomprehending. The eponymous title bearing his mother’s nickname for them.

Kirkland Hamill ’86 is now on a nationwide virtual book tour for Filthy Beasts; he’ll be ready to do it again when the paperback launches in 2021.

In succession, the family loses its fortune, his parents’ marriage falls apart, and Hamill’s mother decides to return to Bermuda. It is there that the consequences of her alcoholism become especially stark. Anxious to resume some resemblance of her previous life as a socialite, she often leaves the boys at home with no food in the house. There’s a regular scramble for money to pay the bills, even as Hamill and his brothers are, via child support, able to attend posh private schools on the island. Within all of this dislocation, Hamill comes to function as a middle-child archetype: he assumes the roles of “responsible” son, his mother’s confidante, and observer of family secrets.

Hamill gets a reprieve—and an opportunity for self-preservation—when he has the opportunity to attend Andover as an upper. Phillips Academy is only a minor focus of the book, but his portrayal of ’80s dorm life saturated by others’ ever-present Grateful Dead music is spot on (at least for this fellow member of the Class of 1986!).

It’s not until he arrives at Tulane University (disclosure: I also went to Tulane.) that Hamill begins to realize the need for self-reflection and healing. You’ll have to read the book yourself to follow his painful and poignant growth over the ensuing decades, including the friendship with a strikingly handsome hall mate whose confidence Hamill longs to have—and which ultimately is the spur that enables him to realize he is gay.

But Hamill’s own self-actualization—and the final resolution with his mother—is still off in the distance.

When we talked, Hamill and I discussed the ways gay children often become the intrepid truth tellers of their families. Filthy Beasts certainly bears witness to the ways in which Hamill is that truth-teller in a family not given to much reflection—either about its privileges or its woes. Later, as an adult, before leaving a career in philanthropy to write full time, Hamill marvels still at the ways in which more altruistic families have chosen to use their wealth.

But Filthy Beasts’ sober reflections—both figurative and literal, for Hamill must ultimately face his own quest for recovery—do not render the narrative a tedious confessional. Drawn from sources written over years, Hamill wrested Filthy Beasts from essays about his mother that were originally shared on Salon magazine’s “Open Salon” discussion group, where they amassed an enthusiastic audience.

Hamill is now turning his fine-tuned analysis of relationships into a draft of a new novel. He admits that finding his “family of choice” has been “the thing that really sustains you,” and he’s examining the dynamics of how that works, how we love—and what happens when those loves are fractured.

In the end, the joy of Filthy Beasts is in witnessing a soul coming into itself. His growth is a delight to observe.

Caroline Langston Jarboe ’86 is a former National Public Radio commentator and has been a contributor to Image: A Journal of the Arts and Slant Books’ “Close Reading” blog. She is currently working on a spiritual memoir about life across the American cultural divide.