December 04, 2020

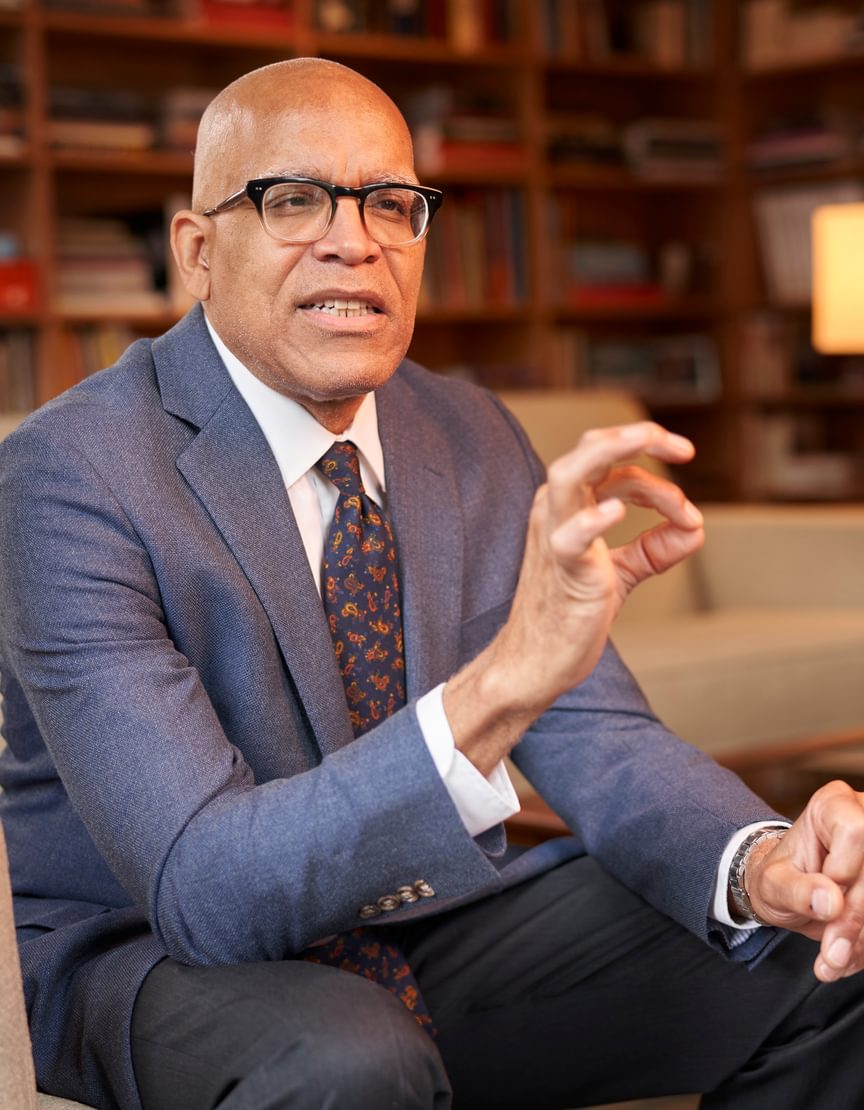

Leading with empathy

Meet Phillips Academy’s 16th Head of School, Dr. Raynard S. Kington, MD, PhD, P’24by Rita Savard

As social injustice, COVID-19, and racial inequality darken the dawn of a new decade, Kington shifts focus to shine a light on solutions.

Pivot.

It might be the most ubiquitous word of 2020, if you don’t count unprecedented. Dr. Raynard S. Kington officially began as Andover’s 16th head of school on July 1, but the COVID-19 pandemic pressed him into service months earlier with rigorous planning for school reopening in the fall.

No stranger to leading a school through crisis, Kington, who was finishing up his 10th year as president of Grinnell College, made the tough call to cancel all in-person classes in March at the Iowa school when COVID-19 hit. What followed was an even more pressing question from parents and educators about the future of in-person classes: When considering how to balance the potential for serious health risks, what do you do?

“Several parents called me up and said, ‘Can you advise us?’” Kington recalled. “Should they stay home, do a gap year, go remote? As a parent, I understand this is a question you wrestle with. The safety and well-being of our children always comes first. I told parents that I would be reluctant to just put everything on hold indefinitely. It made me think a lot about starting this position at Andover.

We cannot choose our time, but we can choose how we deal with what is in front of us, what is here now. During this pandemic, the human connection has never been more important. This is an extremely challenging time, but it is also a time for finding new and creative ways to operate.

”Kington’s experience leading Grinnell through the early stages of the pandemic, and his former work as a physician specializing in research and public policy on the intersection of health and social factors, helped him hit the ground running.

Engaging with colleagues, trustees, and public health officials while still in Iowa, Kington plugged into the Andover community to assess the school’s unique needs and collaborate on a plan to protect students, faculty, and staff.

Under the expert guidance of PA’s medical director, Dr. Amy Patel, protocols and guidelines were set in motion. Among them, an ambitious weekly testing regimen was implemented to keep the community safe as Andover executed a phased reopening in September. And faculty, Kington added, rose to the challenge of learning entirely new ways of teaching, including hybrid, remote, and in-person approaches.

Through it all—the trainings and workshops, the collaborative sessions with colleagues and students, a life-altering pandemic, a combative election season, and nationwide racial unrest—Andover has emphasized the phrase “students first.”

“There have been bumps in the road, as expected,” Kington noted. “The biggest challenge is always uncertainty, where you cannot predict what will happen in a week or month from now. But our community health and safety measures are working well, and we are helping each other settle into new habits of remote learning and engagement.”

“At no part of my education could I have predicted this moment,” Kington said to an audience of students, faculty, and staff in Cochran Chapel last December. This was his first visit to campus after being named head of school.

Kington’s atypical career path or, as he points out, “the unforeseen meandering and unexpected opportunities,” is what makes life interesting. And all of it prepared him for his time at Andover.

Born and raised in Baltimore, Kington, one of five children, credits his schoolteacher mother, Mildred, and his physician father, Garfield, with giving him one of his greatest gifts: “An unshakable belief that I could choose my own path.”

His parents also believed that education is essential, inviting truth, possibility, and freedom.

“I heard this story often growing up,” Kington recalled. “Education was the thing that allowed our family to go from slavery to middle class in one generation.”

Andover’s first African American and openly gay head of school holds an MBA, an MD, and a PhD. His CV includes leading one of the largest studies on the health of the U.S. population at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, serving as interim director of the National Institutes of Health as well as NIH deputy director, and serving as president of a renowned liberal arts college.

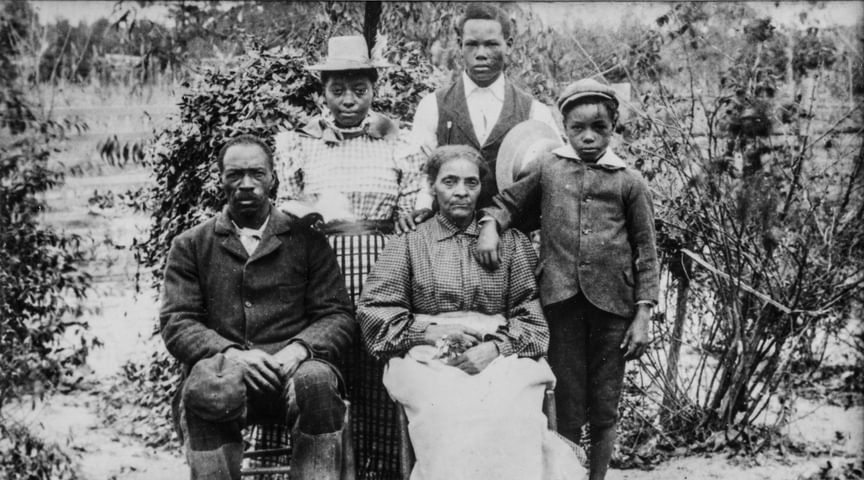

Revealing a piece of his family’s history that day in Cochran Chapel, Kington shared an old photograph, which has been on display in his office since his first job out of college. The photo from the late 1800s, of his great-great-grandmother, her husband, and three children, brought his parents’ passion for education to life and gave it meaning.

He remembers as a kid, his family driving from Baltimore to his maternal grandparents’ home in a close-knit community outside the small town of De Kalb, Texas. The community was founded by freed slaves following the Civil War. The property was acquired through an act of atonement from a slave master, who is also an ancestor—Kington’s biological great-great-great- grandfather. At the end of slavery, he had fought with the Confederacy in Texas, and when the war was over he took one of his plantations and divided it among his slaves, providing a free title to land that helped shape his mother’s family legacy as they forged a strong and independent Black community in the Deep South.

On one of his childhood visits to Texas, Kington and his siblings found a burlap sack filled with family photos tucked away in his grandmother’s closet. They dumped it on the floor and picked their way through the collage. One in particular caught his attention. He didn’t like it.

“Everyone looked rather grim,” Kington explained. But over time, the image has become a daily reminder that, “I am where I am because huge numbers of other people sacrificed.”

The photo shows Kington’s great-great-grandmother with a sprig of flowers in her hand, her two boys leaning closely into her. Their father’s well-worn pants are neatly patched at the knees. And the daughter holds an open book—a nod to the power of education and a signal that the family was literate following a time when it was against the law to teach slaves to read.

“That animated book and small bunch of flowers now mean everything to me,” Kington said. “They symbolize that the family survived the horror of that brutal and dehumanizing system of oppression—a system fueled by greed—and that they survived that system of enslavement with their minds and hearts intact.

“This was also a time of extraordinary uncertainty, when a new system of racial oppression was evolving. And yet, my ancestors had the ability to both prepare for the future by embracing knowledge and to live in the blessing of the moment—to appreciate the beauty in their everyday lives.”

Focusing his attention back to the crowd in Cochran Chapel, Kington said, “Knowledge can be hard and painful as often as it is reassuring and hopeful. And the need to balance knowledge with an appreciation of the mystery of the beauty in the human experience, even in the midst of difficulty and challenge, helps us progress as a community. I hope my time at Andover will be infused with those thoughts and that all of you will help me in shaping the future of everyone who is a part of the story of this special institution.”

Joining the crowd in extended applause were Kington’s husband, Peter T. Daniolos, MD, a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry, and their two sons, Emerson, 14, and Basil, 11.

That was the world pre-pandemic. Months later, Kington has had to deviate from his pre-defined path. Plans have evolved. Schedules have shifted and strained under professional and family demands. Still, Kington’s optimism rises above the chaos.

In September, during Convocation, Kington reminded faculty that their work is essential for a vibrant future.

“I believe there is a rethinking that can occur at these difficult times that helps us see what we might not otherwise see,” he said, “a rethinking that helps us scrape away the superficial and focus on the essential parts underneath.”

On a bright and balmy September morning, Kington was still unpacking and settling into the family’s new home at Phelps House. But his most treasured objects—scores of family photos and a dizzying assortment of books—had been carefully pulled from boxes and arranged in their places.

They offer a glimpse of what matters to the man who cherishes them. He’s a voracious reader. Classics. Biographies. History. The neatly stacked rows of books from floor to ceiling are more than collections of words printed on paper. They are friends and companions that impart knowledge and teach empathy and understanding. They are part of home.

“Whenever Raynard is faced with a challenge, he reads widely and looks for guidance widely,” said Angela Voos, who worked alongside Kington for nine years at Grinnell and served as his chief of staff and vice president for strategic planning.

“He looks for information, narratives, and history to help guide what his next steps are. It’s like being hooked up to an encyclopedia and a news channel. He bathes in what he can know—reading everything he can get his hands on and talking to people. One of his marked characteristics is his openness to hearing all perspectives. He has an amazing talent for bringing everyone to the table and making them feel heard. Regardless of how tough the problem is before you, he creates a safe space of trust to work through it and find solutions.”

Kington’s unwavering commitment to helping others behind the scenes and his mindfulness of the most vulnerable, Voos added, make him an extraordinary leader in the best and worst of times.

“We had one winter that was so very cold—even for Iowa—and we have students on campus who deliver mail,” she recalls. “Raynard saw there was one student that needed boots. He made sure the student got them. The student never knew where the boots came from. Raynard just does things like that. He has a strong moral compass and brings out the best in those around him, leading by example.”

At age 16, Kington entered a combined undergraduate-medical school program at the University of Michigan. The program allowed him to earn a Bachelor of Science degree when he was 19 and his medical degree when he was just 21 years old. He completed his residency in internal medicine at Michael Reese Medical Center in Chicago and was appointed a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar at the University of Pennsylvania. While there, he completed his MBA and PhD with a concentration in health policy and economics at The Wharton School.

As the coursework and the experience of caring for patients during his residency drew him deeper into his craft, Kington discovered the meaningful ways in which he could make a difference in people’s lives, especially in helping underrepresented groups like people of color and the LGBTQ+ community.

In addition to directing one of the CDC’s largest studies on the health of the American people, Kington has helped amplify often-quieted voices, writing articles about public health policy, access, and the effects of race, gender, and ethnic disparities.

In an interview with The Phillipian, Kington confided that in the not too distant past, it would have been unthinkable for someone like him to be leading an institution like Andover, deeply rooted in its ties to the founders of this country—the very same people “who denied the rights and humanness of who I am.”

“I hope it shows how communities, and countries, and institutions—even when they start off with closed doors in many ways—can change, evolve, respond, and get better,” he said.

“To the extent that other people can see me, and see themselves in me, and think there may be more opportunities than they thought about before—that’s the best thing that can happen about acknowledging my identity.”

Arguably, there has never been a more challenging time to lead an academic institution. The Board of Trustees was drawn to both Kington’s unique professional experience and his personal character. But his work ethic under pressure has proven to the board that Kington is devoted to addressing complex issues by immersing himself in the community, collaborating, and creating solutions.

“Raynard is a dynamic leader and a profoundly thoughtful colleague devoted to his community and the well-being of students, faculty, and staff,” said Amy Falls ’82, P’19, ’21 and president of the Board of Trustees. “No one could have imagined our 16th head of school beginning his tenure under such extraordinary circumstances. We are fortunate to have Raynard’s compelling set of professional skills, his reverence for young people, and personal moral compass guiding Andover forward.”

The human connection has never been more important. This is an extremely challenging time, but it is also a time for leaning in and finding new and creative ways to operate.

”Time in a pandemic takes on new fluid forms. Throughout this period, we have all had to pause and refocus to find meaning. For Kington, cooking is an artform and a stress reliever, and the kitchen is where he enjoys seeing people come together to build meaningful experiences.

“During the extended time at home, I learned to cook two things I had always been too intimidated to try: yeast dinner rolls and BBQ spareribs,” said Kington, whose extensive collection of cookbooks and kitchen gadgets would make any foodie gush.

At the end of a busy work day, Kington shifts the focus back to his husband, Peter, and their two sons. Emerson is a junior at Andover and Basil attends Doherty Middle School. “These moments are so important. They’re for slowing down and remembering joy, because the most memorable experiences we have with food are the people.”

That sense of community and working together is the main ingredient Kington envisions for his future at Andover.

Cue to the first day of classes. Even in a virtual world, the broad smile stretching across Kington’s face cut straight through fences. Andover’s new head of school had good reason to feel proud. He was addressing students at the start of a new school year for the first time since officially taking over the Academy’s leadership on July 1.

The first day may have come without handshakes or high fives, but it was filled with hope.

“You are the heart of this community, the energy and spirit fueling our mission to educate youth from every quarter,” said Kington, welcoming more than 1,000 students back to a virtual campus from their laptops.

“We are about to begin one of the most distinctive years in the history of this institution—a time that I suspect we will speak of for many years to come. We will get through this together, and I have absolute faith that when we look back on this experience, we will realize that we have emerged as a stronger, even more committed, and humane community.”