May 06, 2020

Lives lost and the country at a standstill

A look back back at the 1918-1919 Spanish Influenza and its impact on Phillips and Abbot academiesby Paige Roberts

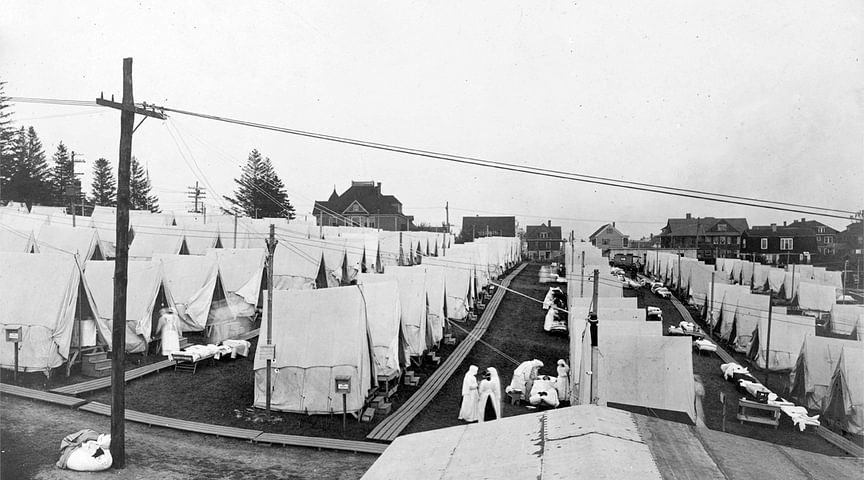

The Spanish Influenza has been called America’s forgotten pandemic. In the face of this 20th-century scourge, the orderly life of America began to disintegrate as the sudden, terrifying disease destroyed the country’s social cohesiveness. Despite the waves of illness, there also was profound social pressure to forget the widespread catastrophe of influenza and the war and to press on toward the future.

On January 22, 1919, the student newspaper The Phillipian reported, “George Vose ’21 died of influenza yesterday morning at his home, East Eddington, Maine. He was well liked by all that knew him. He fell ill scarcely a week ago, and was expected to recover in a short time.”

The influenza had likely started in Kansas in the winter of 1918, traveled to Europe with American soldiers headed to World War I, and returned with troops to Boston in late August 1918, launching a deadlier second wave of disease. The third wave of the pandemic hit the United States in the winter of 1919. In total between 50 to 100 million people around the world, including 675,000 Americans, died of influenza between 1918 and 1920. Young adults—people in their twenties and thirties in the prime of life—were most vulnerable. The close quarters and rapid troop movements of World War I quickened the spread of the disease and helped it mutate.

Despite the sad loss of George Vose, influenza had a relatively benign impact on Andover and its student body, certainly less impact than World War I. There were 593 students at Phillips Academy in 1919. Musical concerts, club activities, chapel services, and athletic contests on campus were postponed during the fall of 1918, but the 1919 Pot Pourri yearbook and the Mirror student literary magazine did not mention influenza at all. Advocating for extra vacation days, a February 5, 1919, student letter to the editor in The Phillipian outlines the minimal impact of the disease at PA as compared to the war.

During the entire period of the influenza epidemic, Andover kept up her scholastic work while all the other secondary schools in the country, with very slight exceptions, remained closed over an average period of six weeks in the months of October and November, thus giving us a head start over them of that amount of time…. The “Flu”, as we all know, was a terrible calamity…. It came as came all the other misfortunes of war. The War, itself, set us all back a great deal.

On September 30, 1918, principal Alfred E. Stearns wrote to a Mr. J.E. Otis of Chicago whose son, Stuart, was applying to Northwestern University. In the letter, Stearns shares that the impact of the virus on campus had been limited writing, “We have a great deal of Influenza about the place, as all New England has, but thus far we have been extremely lucky in the school, the cases have been unusually light. If the good luck continues, the boys will probably be as well off here as they would be at their homes…”

In April 1917, the PA Ambulance Unit set sail for France; during that summer PA graduates entered the military service by the hundreds. Several faculty were already in uniform, and others were to follow that year.

Because the lower limit of the draft age was 21, few current students left for the front lines. On June 14, 1917, trustees voted “That military training be included in the school curriculum for the members of the two upper classes and for all other boys of sixteen years and over whose parents do not disapprove.”

Kenneth Rand, Class of 1910, was rejected by every American and Canadian combat branch due to poor eyesight. He finally entered the Quartermaster Corps but died of influenza on October 15, 1918, before he could reach an Officers’ Training Camp. A published poet, Rand’s private’s uniform contained his last poem titled “Limited Service Only.”

I am not one of those the gods’ decision

Has chosen for that highest gift of all—

The sacrifice, the splendor, and the vision—

To fight and nobly fall:

And yet I know—what though it be but dreaming!

Should the day hang on one last desperate hope,

I—I—could lead one reckless column streaming

Down some shell-tortured slope.

To face the shadow-hell of Death’s own valley

With eyes unclouded and unlowered head—

Know, for an instant, one ecstatic rally

And then be cleanly dead.

The Abbot Courant similarly reported changes in various student activities on the girls’ campus. For instance, on Saturday, November 2, 1918, “On account of the influenza epidemic and the consequent lack of preparation for the usual basketball game, the two schools [Bradford and Abbot] decided to have a Hare and Hound Chase.”

Alumnae notes in the Courant also included flu-related deaths of male relatives. “1889—Alice Conant Wadleigh’s son, Theodore, died in September of pneumonia, following influenza. He had just entered Dartmouth College.” And, “We are very sorry to tell of the death from influenza last fall of Mr. Ellsworth Tower Rundlett, husband of Christine Wyer, class of 1907.”

Other Abbot graduates worked as nurses during the pandemic. Nurses played a critical role in providing care and comforting those who had influenza. Public health practitioners at the time had to strike a balance between educating the public and avoiding panic about influenza. The flu was a mystery that confounded doctors who, before the epidemic, were confident about addressing most infectious disease with new treatments.

Abbot alumnae like Katherine Selden, Class of 1914, was among thousands of nurses who answered the call. According to the Courant, Selden, who was assigned to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, was “summoned in October 1918 by an emergency call for nurses to Camp Humphries, Virginia, to help in the influenza epidemic.” Mary Church and Marion McPherson, both Class of 1917, provided emergency nursing care for “the poorer people during the influenza epidemic in Boston.” And 1918 classmates Margaret Speer, Catherine McReynolds, Katherine Righter, Elizabeth Doolin, and Gay Miller, were ill with influenza in the fall of their senior year, with Miller unable to return until after Christmas.

Paige Roberts has been the Director of Archives and Special Collections at Phillips Academy since 2012. With Abbot Academy alumnae, she completed the Abbot Archives Project in 2017 and is now working on the history of Chinese students at Andover from 1878 to 2000.

Categories: Magazine

Other Stories

Best-selling author Rachel Howzell Hall delivers MLK Day keynote