August 18, 2022

Game On!

Saluting 50 years of Title IX and women in sportsby By Avery Stone ’10 & Rita Savard | Photos by Henry Marte

“Sometimes I forget that I’m a woman in sports,” says Aleisha Roberts ’22. When the boat drops in the water, the girls’ crew co-captain focuses on the only thing that matters—the team’s rhythm. Dialing in each movement, and the space in between, sets the boat from the top of everyone’s stroke.

Keep the starboard oar in the corner of your eye to time up the catch. Relax the slide. Recover on the three-count.

They all lock in together. A band playing in perfect time. This “team first” mindset led the girls to victory against Connecticut’s Kent School during a back-and-forth race in April that continued for all 1,500 meters until Andover pulled across the finish line first.

“But particular moments always remind me of the truth,” Roberts adds, pointing out times when being a female athlete can feel like rowing against the current. “Sometimes it’s boys trying to inflate their egos by comparing their performance to mine. Sometimes it’s repeating myself over and over and still being ignored. Being a woman in sports means encountering challenges of patriarchy and misogyny and having the courage to face it head on because I’m surrounded by other women who understand and love me.”

Painting her nails blue, she adds, and getting the boat past a high stroke rate helps her push forward too.

The impact of Title IX on women’s sports is significant. This game-changing legislation—prohibiting sex-based discrimination in any school or education program that receives federal funding—was signed into law on June 23, 1972. Before Title IX passed, only 1 percent of college athletic budgets went to women’s sports programs and, at the high school level, male athletes outnumbered female athletes 12.5 to 1, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation (WSF).

“Sports will not be easy, and only you can decide if it’s worth it. If it isn’t, know that it is absolutely alright to seek joy elsewhere. If it is, never lose sight of what you’re fighting for and let absolutely nobody take that away from you.” - Aleisha Roberts ’22 | crew

“Sports will not be easy, and only you can decide if it’s worth it. If it isn’t, know that it is absolutely alright to seek joy elsewhere. If it is, never lose sight of what you’re fighting for and let absolutely nobody take that away from you.” - Aleisha Roberts ’22 | crew

While Phillips Academy does not receive federal financial assistance and is not subject to Title IX, the waves of change for gender equity that swept across the country greatly impacted the Academy, as the law dovetailed with a landmark event in the school’s history. In the fall of 1973, PA became coed. The first generation of female students at PA chose to blaze their own trail in athletics, leaving legacies of excellence and advocacy.

“We have come so far since those who fought the fight to see Title IX pass,” says Lisa Joel, Andover’s athletics director and girls’ varsity soccer coach. “We stand on their shoulders and have the opportunities we have because of the path they paved.”

Fifty years from Title IX’s inception, Andover’s athletics community weighs in on the growth and obstacles in women’s sports.

“I think we’ve gotten to the point where women can exist and thrive in high-level sports,” Roberts says. “In the future, I’d love to see a world where it is no longer a battle to prove that we belong.”

Modern Pioneers

When Dianne P. Hurley ’80 arrived in the mid- 1970s, girls’ ice hockey was available for the first time. She jumped at the chance to join the team.

“Because we showed so much enthusiasm and dedication, girls’ ice hockey became a varsity sport the very next year,” Hurley recalls. The team had a packed game schedule and in Hurley’s senior year they were undefeated—which earned the team a steak dinner hosted by Head of School Ted Sizer, who had vehemently fought for and ushered in a coeducational Andover.

Hurley’s time playing hockey at Andover led to a four-year hockey career at Harvard—as well as one year of soccer and rowing intramurally. “Andover taught me to love many diverse sports and to be comfortable trying new sports,” Hurley says.

Other women broke gender barriers on teams

that were already well established. Devin Adair ’82

became the first female coxswain on the boys’ varsity crew team at Andover. Her career was shaped

and inspired by coach Martha Beattie.

“The women’s crew team was really serious and ambitious because Martha had high expectations for us,” Adair says. “She had been a champion oarswoman at Dartmouth and participated in the women’s national team camps. She was the first female athlete role model I had ever encountered and encouraged me to try out for the junior national team, helping arrange for me and some other ambitious female rowers to train in the summer. She mentored us to aim high and try hard. I was awed by her.”

Adair became close friends with a group of male rowers and was eventually asked to try out for the boys’ team. She went on to Harvard and became the first female coxswain on the men’s heavyweight crew team, leading them to a legendary victory against Yale. There wouldn’t be another woman on men’s crew for 30 years.

“The confidence and professionalism I developed as an athlete at Andover was crucial—seriously, the most important factor in my success at Harvard,” she says. “I don’t think I could have withstood the pressure of a Division I all-male program without the seasoning and training I had at Andover. I walked into the Harvard boathouse with total confidence that I could be a contender. Without that drive and confidence, I would not have lasted one season there.”

I call myself the pebble in the shoe. It’s constant work, and it shouldn’t have to be, but we have to keep saying and believing, ‘my life is as important as yours.’ We have to keep chipping away.

”Becky Calder ’94 had a similarly formative experience playing basketball.

“My coach in nearly every sport and every season was Karen Kennedy—or just ‘Coach,’ as we called her—and she showed us what non sibi looked like every day. She coached us, taught us, parented us, fed us, sacrificed for us, challenged us, and loved us like her own. She showed us what hard work, grit, and determination looked like and what it was for: our team.”

The lessons Calder learned through her time at Andover—don’t give up and work hard for your team no matter what that team looks like—helped her launch a successful basketball career at the Naval Academy followed by a 24-year career in the U.S. military.

“My team turned into a squadron of F-18 pilots, and we quickly found ourselves at war after the events of September 11th,” she says. “The same hard work and sacrifice—the same non sibi spirit that I was taught by Karen [Kennedy] directly carried over onto the battlefield of Afghanistan and Iraq. We didn’t quit, we didn’t give up, and we worked hard.”

Calder says she’s often asked why she joined the military. “If I am answering that question honestly, it was because of basketball,” she says. “My love for basketball started at Andover and Andover truly taught me what it means to serve others.”

Before Title IX—and a four-decade career coaching girls’ sports—Calder’s mentor, Karen Kennedy, blew out her knee playing field hockey. Rules at her Danvers, Mass., high school prohibited trainers from treating female athletes. A surgeon was reluctant to operate, remarking that the scar would “look ugly” when she wore a bathing suit.

That was just the beginning of a long road strewn with obstacles Kennedy would be forced to confront because she was a female who wanted to play sports. She was even told by a male coach in college that “girls will never play soccer,” which he punctuated with a warning: if she stepped onto a field, she’d wind up in a hospital. “Female athletes were always as fierce as their male counterparts,” Kennedy says. “But 50 years ago, the narrative was different.”

After college, Kennedy landed a job coaching the first girls’ soccer program at Andover High School. She wrote a letter to the same college coach who told her girls would never play. “I wanted to share the news and tell him times were changing and that going forward, I hoped he would treat female and male athletes better,” she says.

Some 30 years after Title IX became law, in the ’90s, Kennedy, now an instructor in athletics at Andover, recalls a major victory when 11 seniors from the girls’ varsity soccer team went on to play collegiate sports, many at the Division I level. This was, Kennedy adds, “extraordinary” proof that girls could in fact compete at a high level.

“I call myself the pebble in the shoe,” Kennedy says. “It’s constant work, and it shouldn’t have to be, but we have to keep saying and believing, ‘my life is as important as yours.’ We have to keep chipping away.”

We have come so far since those who fought the fight to see Title IX pass. We stand on their shoulders and have the opportunities we have because of the path they paved.

”Empowerment Through Sports

By the turn of the millennium, the effects of Title IX were clearly visible as female students be- gan coming to Andover with significant athletic achievements. Hee-Jin Chang ’05 swam for South Korea in the 2000 Summer Olympics in Sydney Australia, when she was just 14 years old. So it’s no surprise that while attending Andover she set school records in nine of 11 swimming events—two of which still stand today. Chang went on to swim at the University of Texas at Austin and in the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

1995 Girls’ Diving. Photo courtesy Phillips Academy Archives.

1995 Girls’ Diving. Photo courtesy Phillips Academy Archives.

But Chang’s Andover athletics story has just as much to do with what she didn’t excel at.

“I was a great swimmer when I joined Andover,” she says. “But I did not want to—or was afraid to—try new sports.” The best thing about Andover athletics, Chang notes, was that she wasn’t allowed to be just “the swimmer”—a gift she attributes to Martha Fenton ’83, P’17, ’21, ’23, current girls’ hockey coach and former athletics director.

“Martha encouraged me to try other sports, like rowing,” Chang recalls. “And I loved it. I always think of Martha when I am afraid to venture into new areas in life—she’s always in the back of my mind, encouraging me to make the leap into the unknown.”

Others also tried new sports, which ended up becoming a central focus in their lives going for- ward. Case in point: Kassie Archambault ’06, who decided to join the wrestling team her first year with no prior experience. By her lower year, she’d made the varsity line up. The support she received at Andover felt groundbreaking for her.

“When I started, I took for granted how supportive our coaches and team were of girls wrestling,” Archambault says. “Once I made varsity, I realized that wasn’t the case at other schools. We were certainly ahead of the game.”

This dynamic played out in competition: “People thought we were making a statement by putting a girl out as the varsity 103-pounder, not realizing that I had beaten two other boys for my spot. I had boys who refused to wrestle me in competition and therefore would just forfeit.”

Although Archambault didn’t wrestle in college, she returned to the sport when she came back to Andover in 2012 as a teacher. She is currently chair of the Russian Department, assistant girls’ varsity lacrosse coach, and head varsity wrestling coach, having recently been named New England Preparatory School Wrestling Association Coach of the Year.

The wrestling world has come a long way since her time as a student, Archambault says. And Andover has continued to help pave the way. “When I was an athlete, we had to look elsewhere for all-girl tournaments—my coaches would take me to the local ones and then my family would take me to tournaments that were further away,” she says. “Now all prep schools are on board with girls wrestling and there is a girls’ division at the New England championships and the Prep National Championships. I could never have dreamed of that as a student.”

Julie Wadland ’06 also cites Andover athletics as laying the foundation for her life beyond the Hill. She earned 12 varsity letters—in soccer, ice hockey, and lacrosse—but when asked which experiences stand out the most, she points to Andover’s biggest rival to the north.

“To me, Andover-Exeter embodies the spirit of athletics at Andover—it strikes a balance between competition and community,” Wadland says. “I always found the spirit of connection between fellow teammates, faculty and staff, alumni, and families very moving; it was and is a demonstrative example of how we can accomplish far more—and have fun along the way—by coming together and supporting others.”

Wadland went on to play lacrosse at Dartmouth College; her junior and senior years, she captained the team. In 2019, she was inducted into the Andover Athletics Hall of Honor. Today, Wadland works as an associate director of admissions at Concord Academy, a private coeducational high school. Working with young people every day, Wadland draws upon her Andover experience.

“The support I received from my Andover coaches, friends, teammates, and teachers offered me a foundation built on confidence, reassurance, and love in the pursuit of my goals as a collegiate student-athlete,” she says. “That pride, tradition, and love continue to frame how I pursue my own work today.”

Although her experience as a student-athlete was overwhelmingly positive, Wadland acknowledges the many hurdles that lie ahead. “Female-identifying student-athletes were well-respected during my time at Andover,” she says. “We are beginning to see that similar respect extended to women in professional sports—increased media coverage, slight compensation increases. But progress remains slow.”

The support I received from my Andover coaches, friends, teammates, and teachers offered me a foundation built on confidence, reassurance, and love in the pursuit of my goals as a collegiate student-athlete.

”

One Win, Another Challenge

Over five decades, Title IX has paved the way for glimmers of progress. In May, the U.S. women’s soccer team settled a lawsuit with the sport’s national governing body, which pledged to equalize pay for the men’s and women’s national teams. But what should have been a revolutionary step forward in gender equality has its shortcomings.

“Equity and equality are not the same,” says Aisha Jorge Massengill ’88. The vice president and deputy general counsel of employment and teammate relations at Under Armour, Massengill was appointed to PA’s Board of Trustees in July.

Massengill made history at Andover as the first athlete to earn 12 varsity letters in four years (in volleyball, softball, and basketball). She went on to play Division I softball at Boston College, where she studied law. Sports helped show Massengill what she was capable of and taught those who watched her never to underestimate what a female can do.

“Sports helped change how women saw themselves and how the rest of society saw us,” Massengill

says. But now, she adds, that feels at risk.

A day after celebrating the 50-year landmark passage of Title IX this past June, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, declaring that the constitutional right to abortion, upheld for nearly half a century, no longer exists. The decision, which put the power in the hands of state governments, prompted abortion rights to be totally or near- totally banned in 26 states.

“While there has been tremendous progress in women’s athletics, we cannot be complacent,” Massengill says. “The Roe decision and the state laws that have since followed highlight that the gains we have made are tenuous at best. Our right to live and compete on equal footing—and to have agency over our bodies—must be vigilantly protected.”

As optimistic as she feels about women’s sports, Athletics Director Joel reminds that we still have a long way to go. “All female athletes deserve equal access to top-tier facilities, locker rooms, trainers, coaches, equipment, and uniforms—the same as the boys deserve,” she says. “We also must under- stand that the news coverage

of girls’ and women’s sports often falls short. The stories of female athletes at all levels must be told and celebrated—they cannot be the side or back story but should be right alongside the stories about male athletes.”

Joel is also quick to recognize the importance of men who fiercely advocate for equality—like her friend and mentor, retired Andover football coach and emeritus athletics director Leon Modeste. “Leon was truly ahead of his time,” Joel says. “He not only fought for girls’ sports, but also took action by hiring women coaches.”

Our girls’ teams are as driven and aggressive as any of our boys’ teams. That’s the Andover way.

”When Modeste joined the coaching staff in 1986, changes were underway. Coaches, he stresses, play a fundamental function, working closely with athletes to develop physical, technical, and psychological improvements. In addition to exceptional coaching, Andover also prioritized equal access to facilities and equipment.

“Things really started to change when people began getting turf fields,” Modeste says. “Some schools would put boys on their main field and place the girls on secondary fields that weren’t as visible or well maintained. We were reluctant to play schools that put our girls on other spaces.”

When the Academy switched to turf, Modeste made sure the field hockey lines were permanently painted on the field in ad- addition to the football lines.

“This shouted to the world that both these teams were equally important—literally playing on the same turf,” he says. “Our girls’ teams are as driven and aggressive as any of our boys’ teams. That’s the Andover way.”

On campus today, female athletes continue to be trailblazers in their sports and are unafraid to point out the challenges they face—and the progress that remains for gender equality more broadly.

While crew captain Roberts says that team sports benefit her in many ways, including inspiring gratitude, she also recognizes the road toward equality is long and winding.

“An important issue for women in sports right now is the hate that is directed toward women who occupy additional marginalized identities—trans women, women of color, women with disabilities,” she says.

Many of the student-athletes, as well as alumni and coaches, refer to the case of Brittney Griner, a seven-time WNBA All-Star, who was detained in Russia on February 17 for carrying marijuana concentrate (cannabis oil) in her luggage. The star center for the Phoenix Mercury (who was sentenced to nine years in prison at the time of publication) was in Russia to play during the WNBA off-season. Roughly half of WNBA players compete overseas in the off-season to augment their domestic income. Griner’s counterparts in the men’s league make more than 200 times the maximum WNBA salary.

“She’s every bit the Tom Brady of her sport,” Modeste points out. “It is crazy that WNBA players make so little that they have to go overseas to supplement their income. They work just as hard as male players do, yet you can’t deny that more people pay to see a team like the New York Knicks lose instead of the Liberty (WNBA), who actually win games! That’s a societal problem.”

While society catches up, the current generation of female athletes presses ahead. Roberts, who graduated in June, would like to see more room for women to not have to be incredible at a sport to be respected.

“I want women to be comfortable trying sports just for fun, with any body type, at any skill level, and feel like they belong,” she says.

Shea Freda ’24, who plays field hockey, ice hockey, and lacrosse, hopes to see more girls play longer—girls are dropping out of sports at two times the rate of boys by high school (around 51 percent), according to the WSF. Freda also hopes to turn on the TV in 10 years and watch “women’s sports broadcast equally to men’s.”

“We battle being overlooked, underpaid, and underestimated,” Freda says. “As I see it, each female athlete may be a competitor, but we compete for each other.”

Soccer and track athlete Myra Bhathena ’22 likewise believes that female athletes are bound not only to one another, but also to women throughout history who have fought and continue to fight for equality. She often feels the weight of the struggle.

“Every time I step onto the field or track,” says Bhathena, “it can feel burdensome to continuously have to prove my—and all women’s—place in athletics. Being a female in sports should not be an exception, although we still often feel like outsiders in such male-dominated spaces. To me, being a female in sports is a privilege. I hope that soon it will become an empowering norm.”

While there are still barriers to break in reaching equality, women, the students echo, are more visible in sport now than ever before. And they aren't backing down from leveling the playing field.

“Find the sport than makes you happy, less stressed, or gets you excited,” says Sakina Cotton ’24, who wrestles and plays Ultimate Frisbee. Prior to games, she likes to queue up Alicia Keys’ “New Day” to get in the zone.

“We are still working on amending the sports disparity between males and females,” Cotton says. “But know there are many people out there who want to see you shine and support you. You just have to find your people—and never stop believing in the power of you.”

Lead Image

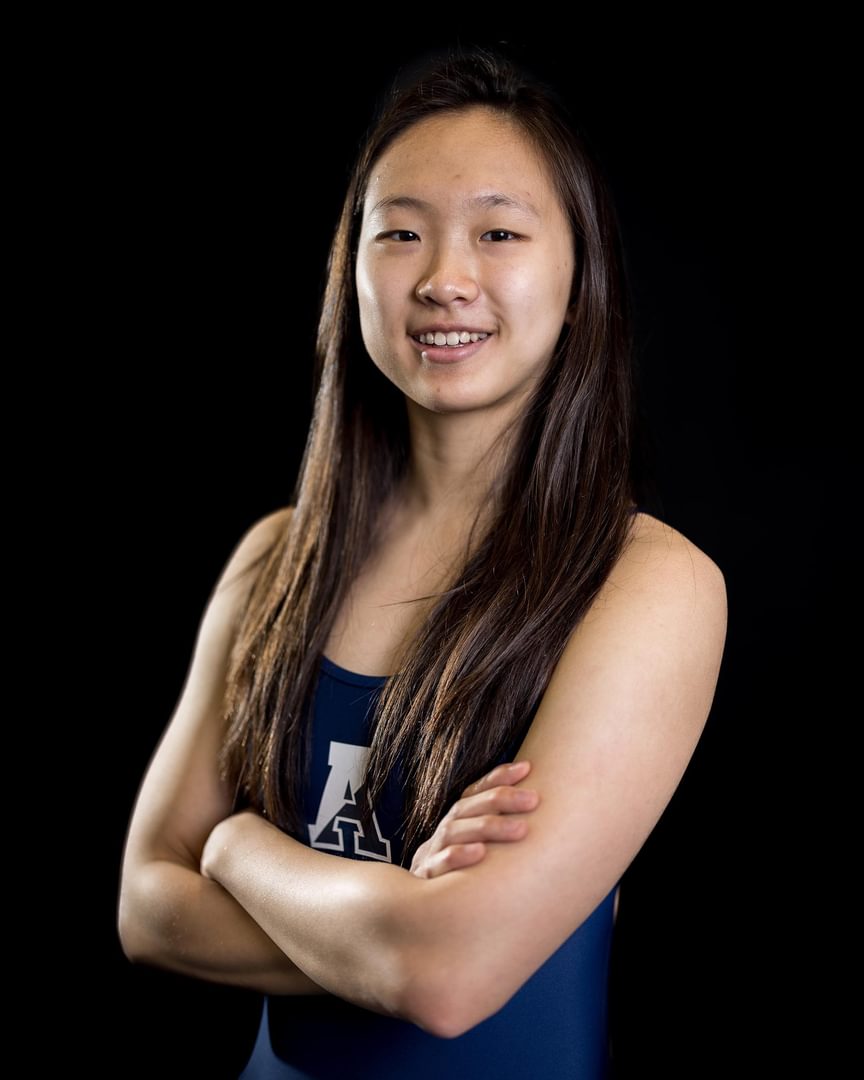

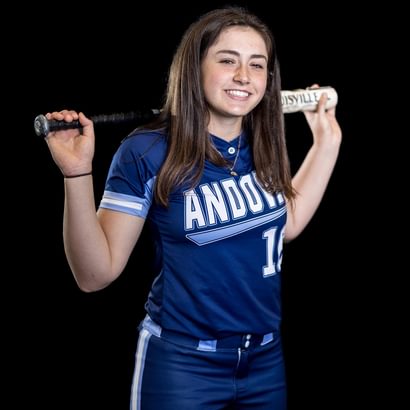

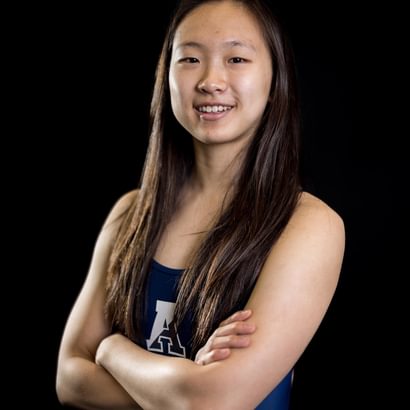

Top row: Kiera Suh ’22, Rachel Neyman ’22, Aleisha Roberts ’22, Myra Bhathena ’22

Center row: Kiley Buckley ’23, Migyu Kim ’25, Elissa Kim ’24, Hannah Justicz ’22

Front row: Emily Mara ’25, Shea Freda ’24, Kennedy Herndon ’23, Sakina Cotton ’24