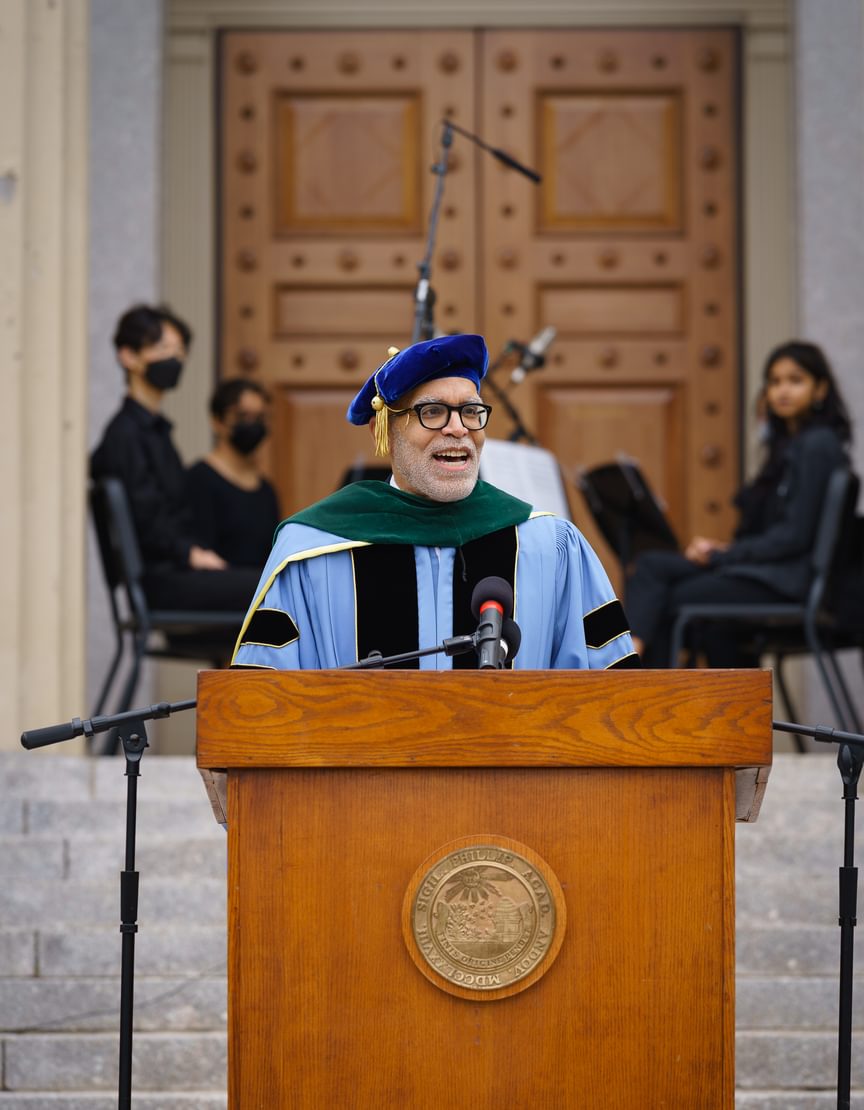

May 13, 2022

Investiture address

Delivered on May 7, 2022by Raynard S. Kington MD, PhD, P’24

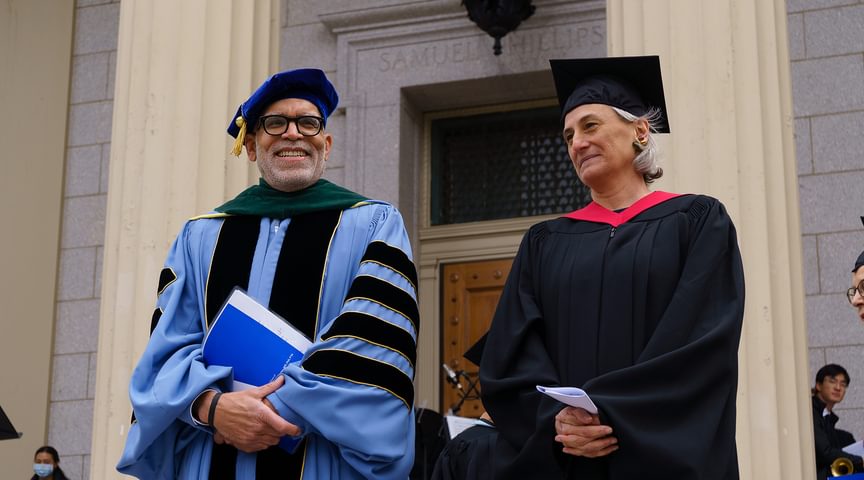

Thank you for that lovely introduction and thank you—faculty, staff, faculty emeriti, and students, trustees, alumni, and families. Thank you for helping to celebrate this remarkable institution. Amy Falls, thank you for opening my eyes to a very special opportunity and for your unwavering partnership.

As you may know, Amy is the first woman president of the Board of Trustees (Abbot or Andover). She, too, is making history.

I want to thank a few people who have been particularly influential in my journey. First, my late parents, Mildred Shavers Kington and Dr. Garfield Douglas Kington. My parents gave me perhaps among the greatest gifts parents can give a child: they gave me an emancipated mind to imagine a life and a career different from theirs and different from anyone around me growing up. They also imbued in me a deep respect for the incomparable power of an educated mind.

I would also like to thank two of my mother’s sisters. My late Aunt Myrtle was my mother’s twin, and she and my Uncle Bernard were especially kind and supportive when I entered the University of Michigan a month after turning 16 years old, regularly driving to Ann Arbor from Detroit to take me out to dinner and then, I later learned, reporting back to my parents. I would also like to acknowledge my Aunt Mattie, who is 102 and watching from her home in Nashville.

Finally, I would like to thank my spouse, Dr. Peter Daniolos, without whose support and love I would not be here, and our children, Emerson and Basil, who overcame their initial strongly negative response when told of the possibility of our family moving away from the small town in Iowa where they had spent the bulk of their lives. I think they have mostly forgiven us.

I struggled with this speech, in part because I am uncomfortable with a ceremony with me at the center. There are a thousand reasons why we did not need to have an investiture, and yet I remembered something my mother had told me when I was a teenager making yet another snarky comment about an old-fashioned minister I didn’t think much of from her church and expressing dismay that she could remain a member of that church. She told me, in her best elementary school teacher voice, that the church is not the minister; it is the people, all the people from its founding onward. The minister at any one point in time is a small, small slice of the church. So, I was reminded that though I am the one being “invested”, I am really a small slice in the arc of this school, which of course, includes the history of Abbot Academy and the merger of Phillips and Abbot to become one. When I thought about the people of this community, and its mission, I found that notion reassuring.

Another cause for my struggle is that I am uncomfortable with celebrations of beginnings, whether a beginning such as my investiture or an anniversary of a beginning, even birthdays.

In 1987, when the country was celebrating the 200th anniversary of the Constitution, I was a faculty fellow at DuBois College House at Penn and in spite of my close proximity to where that document was ratified, I could not feel any of the celebratory moods. In fact, I found the entire celebration irritating. Perhaps I was uncomfortable with the event because it was just one year after the infamous Bowers v. Hardwick Supreme Court decision upholding the Georgia law making intimate homosexual relations between consenting adults illegal. That ruling included a concurring opinion written by Chief Justice Warren Burger, who was the chair of the committee overseeing the 200th anniversary celebrations that year. Or maybe I was just channeling the traditional African American discomfort with blindly celebrating many elements of the history of this country when the gap between its ideals and its reality—even today—is so well-known by our community.

During that time, one of my heroes, Thurgood Marshall, gave a speech about that bicentennial celebration that was defiantly not in line with the general tenor of what almost everyone else was saying. I have thought a lot about that speech recently.

Most notably, Marshall said that he refused to celebrate the flawed document that is the Constitution. He said this about the changes in the Constitution that followed the so-called “Miracle in Philadelphia”:

The men who gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 could not have envisioned these changes. They could not have imagined, nor would they have accepted, that the document they were drafting would one day be construed by a Supreme Court to which had been appointed a woman and the descendent of an African slave. “We the People” no longer enslave, but the credit does not belong to the Framers. It belongs to those who refused to acquiesce in outdated notions of “liberty,” “justice,” and “equality,” and who strived to better them.

He went on to say: …the true miracle was not the birth of the Constitution, but its life.

I loved that idea of celebrating the life of the Constitution rather than its birth. It allowed me to find a place for myself in that celebration in 1987 and now in this celebration. So, I see this investiture not as a celebration that is about my beginning, but instead this is a celebration of the life of this institution— a way to note that this school has made it this far and has changed so much, just as our Constitution has, and that I could be appointed to lead this school. I see this celebration as a turning of the page from one chapter to another in the long life of this great school.

I know that there are those who see my appointment as the first African American head and the first openly gay head as especially notable, and I do as well. I never forget that I am where I am not only because I worked hard but also because countless other people sacrificed to open doors that I could walk through. If this ceremony had been taking place 10, 5 or even 3 years ago, I would l have stopped there in commenting on the significance of what is notable about my appointment.

Even three years ago, I would not have focused my comments on my race or sexual orientation. Not because I am in any way uncomfortable with those elements of who I am—quite the contrary. But the shifts in our national discourse and our deep societal divisions with respect to race and sexual orientation and gender that are manifesting daily serve as a stark reminder that we can never rest, that all rights or privileges are not guaranteed forever, that we must fight to keep them. The need to be vigilant remains because the time when my appointment would have been unthinkable is not that long ago.

We are living in a troubling time, when some people do not like where we have arrived as a democratic society and where we might be headed, when some people are surely not thrilled by my double-first status. They do not want to stand athwart history and yell “stop”; they want to barricade before history with weapons drawn, spewing bigotry and yelling: “Turn around, turn back.” They want us to return to a flawed memory of a past America that existed as great only in the minds of a few.

But great for whom?

We will not go back. We cannot go back. Because of places like Phillips Academy whose constitution espouses the crucial unity of knowledge and goodness, we will not go back. Our minds and our knowledge and our experiences and our imaginations move us forward. That is a testament to the power of education.

The opening of the doors that I have walked through is deeply tied to the power of knowledge, of education, like the transformative education that Phillips Academy has provided for almost 250 years. There is a reason why it was against the law to teach my great grandparents to read and write as enslaved people. Those who benefited from that wretched institution of slavery knew the power of opening a mind, the power of knowledge that so clearly gave lie to racist notions of a hierarchy of humans. And that is why my great grandparents and so many others worked so hard to make sure their children were educated. We are not going back.

So today we are celebrating all the people who brought this institution this far, who helped this institution step by step to move closer to the more noble ideas at the base of our school’s originating constitution and our country’s constitution. I want to especially celebrate all those who helped this school change and constantly aspire to become better, to remain relevant and to lead in a changing world.

It seems only appropriate that today marks the first time that the Head of School Investiture is held on the Richard T. Greener Quadrangle, named after the first African American graduate of this school. This iconic location was named through the generosity of an anonymous donor and honors the legacy of one of America’s trailblazing advocates for racial equality. A member of the Phillips Academy Class of 1865 and a deeply loyal alumnus, Richard T. Greener was an active and notable voice for the rights of Black Americans during and long after the Reconstruction period, serving as both dean of Howard University Law School and associate editor of Frederick Douglass’s newspaper, New National Era. A scholar and teacher, lawyer and diplomat, he led by example and touched the lives of faculty and students of this institution.

When we speak about Greener we often note that he was also the first black graduate of Harvard. But there is another part of his life that is more painful to remember but worth reminding ourselves about today. Several years after he graduated from Harvard, he became the first Black faculty member of the University of South Carolina, the only public university in the south that integrated during Reconstruction. He also took the role of the school’s librarian and enrolled in its law school. He was among the first African American students to graduate from the University of South Carolina’s Law School. But as Reconstruction came to an end, Greener had to leave that university after it was closed and then reopened as an all-white school. Rights and privileges can be taken away, as Greener’s were.

Of course, there is no doubt that we have made incredible progress over the history of this school. That progress is a testament to the faculty’s devotion to Andover’s mission and to their willingness to remain nimble, themselves being students of the craft of teaching. It is also a testament to those who came before me and ably led this school during rewarding and challenging times. Just think about recent history and the nearly 25 years of leadership between Barbara Landis Chase and John Palfrey (1994 – 2019). You quickly understand what is necessary to keep pace and evolve with the times to move forward. All this to meet our mission in service of students.

And my taking this position is also real evidence of continued progress. But at this time when dishonest narratives of stolen elections are used to justify the denial of voting rights, when leaders energize voters with their homophobic and transphobic rhetoric, the education we offer has never been more important.

And I believe that an essential part of that education is the free engagement with ideas, including ideas that some of us may find to be odious. I don’t aim for a false notion of neutrality. I am not neutral on many controversial issues, especially those that are tied to our values and our mission. For those issues, in particular, we as an institution should not strive to be neutral. Not all ideas are equally valid or important or true. But I believe in engaging with those odious ideas because bringing them into the light is the only way to demonstrate what is wrong about them. I welcome that engagement because I am confident that openness will lead to better ideas, ideas that will help to continue to bend the moral arc of the universe toward justice.

I have tried in my comments today to walk a fine line. To be honest about how I feel about the time in which this investiture is taking place, the perilous moment we are in as a nation. But also to show that I am hopeful, because I am hopeful. So I will end with a piece from The Fire Next Time written by James Baldwin, another of my heroes.

He wrote:

It began to seem that one would have to hold in the mind forever two ideas which seemed to be opposition. The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are: in the light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustice is a commonplace. But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength. This fight begins, however, in the heart and it now had been laid to my charge to keep my own heart free of hatred and despair.

Great schools exist at the intersection Baldwin described so eloquently, at that point of tension—the intersection of helping our students to understand the world as it is with all of its flaws, with ideas that make us uncomfortable and sometimes with painful knowledge that can even tempt us to hate and despair, while empowering students with hope grounded in knowledge, with the intellectual tools to change what needs to be changed, to change what is wrong with our beautiful, broken world.

And we must help our students to discern the truth. Today, the truth is that it is hard for many of us to keep from despairing. But whenever I am in one of those moods, all I have to do is take a walk across this beautiful campus and see our faculty and our staff, who make this place work, and our students, especially, with their diversity, their intelligence, their eagerness to explore and understand the world around them in all its complexity. Seeing them is all I need to renew my faith in the future of this extraordinary country and this extraordinary institution’s place in this country and the world. Our incredible students are my hope, they are the reason why I get up every day and cross Main and walk across the great lawn, past the sign for Greener Quad, enter George Washington Hall and sit at my desk and begin my day. They make it all worthwhile.

Thank you for listening.