May 17, 2022

Saving Abbot

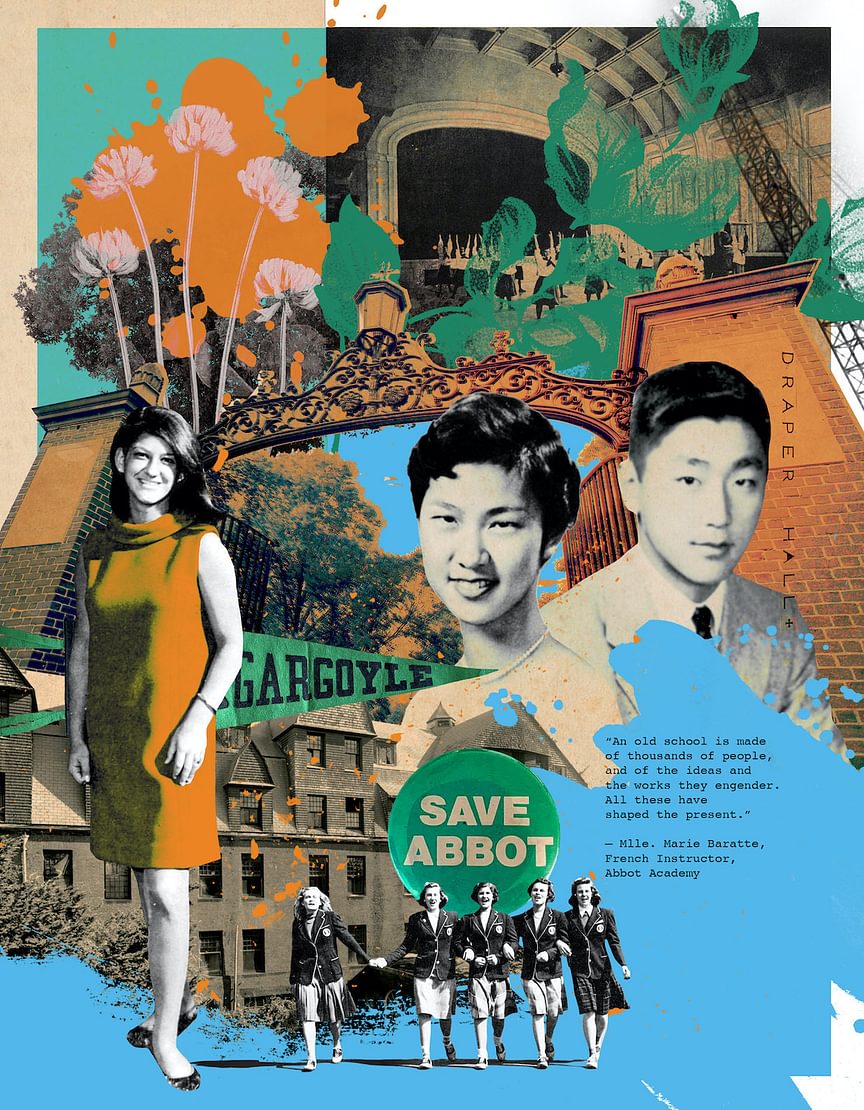

How love, perseverance, and strong women protected a legacy for future generationsby Rita Savard & illustrations by Eleanor Shakespeare

The poet and author Julia Alvarez ’67 famously said, “Each of us will have to make the choices that allow us to be the largest versions of ourselves.”

For generations of women—who did not choose their time but felt the fires of ambition to do and be more than society allowed—Abbot Academy was much more than bricks and mortar. It was an intentional community ahead of its time, pushing young women to recognize their strengths and write their own narratives.

Soon after opening in 1828 as one of the first educational institutions in New England exclusively for girls, Abbot, writes Faculty Emerita Susan McIntosh Lloyd in her book A Singular School: Abbot Academy 1828–1973, earned a reputation as a “protected space in which students might develop their independent powers, free from the pressures for early marriage that alternately excited and harassed so many young women of the time.”

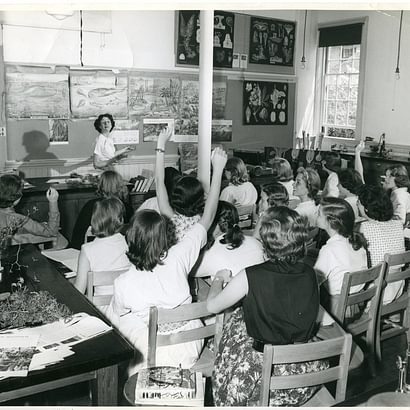

Girls were encouraged to ask questions, offer their opinions, engage in provocative debate, and prepare to stand their ground in any battle of wits.

“All of this,” explains Elaine “Lanie” Finbury ’68, P’99, “was happening in classrooms where you didn’t have to worry about being overlooked by teachers or have your voice drowned out by boys. Sadly, for too long, that had been the norm for women in the school setting. But Abbot offered something different.”

Abbot’s reputation for opening doors and shaping women into thought-leaders is why alumnae like Finbury, Barbara Timken ’66, Frances “Frankie” Young Tang ’57, and many others formed a village to save the campus from a wrecking ball—a very realistic proposition in the 1970s and 1980s, when the Abbot property was eyed for uses from retirement housing to a hotel and conference center to multifamily apartments for the town of Andover.

Without the iron-clad determination of these alumnae who never gave up on what Abbot gave to them, the legacy of Abbot Academy and its vital role in the story of Phillips Academy could have been reduced to just words on printed pages. Instead, Abbot’s historic buildings and the Sacred Circle remain—proud emblems of the strength and purpose of women’s education.

They also tell another story in PA’s reason for being—to offer life of the mind and growth of the spirit to ongoing generations of students.

The Times They Are A-Changing

Somewhere in Draper Hall, welling up over a portable turntable, a powerhouse voice filled with determination, tenacity, and emotion echoes down a hallway: “You better think (think), think about what you’re tryin’ to do to me. Yeah, think (think, think). Let your mind go, let yourself be free…Oh freedom, freedom, freedom, yeah, freedom.”

Aretha Franklin’s timing couldn’t have been better for adding a layer of anthemic feminism to a teenage girl’s dorm room. The changes of 1968 were palpable on campus. In classrooms filled with young women, via a curriculum designed to challenge, inspire, and empower women—that was largely taught by women—a great awakening was taking place.

Frances "Frankie" Young Tang ’57 and Oscar Tang ’56 at an Abbot prom. Courtesy photo.

Frances "Frankie" Young Tang ’57 and Oscar Tang ’56 at an Abbot prom. Courtesy photo.

“From Civil Rights to Vietnam, I can’t think of any one of us who escaped the impact of those years,” remembers Finbury.

The assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, just months apart, became lightning rods for the Abbot girls. Hours were spent discussing politics, people, women’s leadership, and how they could have the greatest impact.

The Civil Rights Movement was creating a climate of protest across the nation as activists demanded equal rights, protections, and new positions in society for Black Americans and people of color. This time of deep cultural changes was also altering the role of women, who fought for access to careers of their choosing—and they expected to be paid the same as men.

Finbury transferred to Abbot as a day student in 1965, when Mary Hinckley Crane, whose portrait hangs in the Abbot Hall School Room, was principal.

“It was an incredible three years,” Finbury says. “I had outstanding classmates, many of whom remain my closest friends today. The atmosphere was buzzing with intellectual challenges and physical education was also an important part of each day. Everybody played a sport and that has stayed with me throughout my life as a source of balance. I danced, played tennis, field hockey, and lacrosse. It was a time of intense learning—mental and physical—and creativity. It’s the time in my girlhood when I began to realize the diversity of distinct and outstanding talents that all girls possess, but not all were presented with the pathways to tap into their power and potential.”

She praises English instructor Jean St. Pierre, who inspired a passion for books and helped countless girls embrace the liberating might of their own imaginations. But it was American History instructor Mary Minard who, by teaching history’s vital role in the development of both a national and an individual sense of identity, helped Finbury recognize her true calling.

Abbot instilled in us profound strength of character. It became important to do something meaningful with that and not simply follow the paths we started on.

”After graduating in 1968, Finbury went on to study architectural history and preservation management, eventually earning a master’s degree from Boston University. An early pioneer in this field, BU demanded graduate-level knowledge of architectural history, federal and local housing laws, adaptive reuse, and economic analysis of preservation. Finbury’s unique skill set launched her on an entrepreneurial career path to becoming a leading advisor, advocate, and expert on preserving and restoring historic buildings.

“The biggest gift Abbot gave that still benefits me today?” ponders Finbury. “A sense of horizon. Abbot showed me I didn’t have to be constrained by what was expected or what was considered ‘normal.’ I chose a difficult career path because Abbot gave me the tools to navigate the road less traveled for women at the time, and to navigate it successfully.”

Realizing the American Dream

Gaining a new perspective is life changing. The world Frankie Young saw through her dorm window was filled with possibilities and campus architecture she admired as art. Young came to Abbot out of the chaos and tragedy of war. Her father, Clarence Kuangson Young, was a Nationalist Chinese diplomat who was the Chinese Consul General in Manila at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack. He was captured by the Japanese during World War II and executed in the Philippines.

The youngest of three daughters, Frankie was just 7 when she traveled to the United States on a troop ship with her widowed mother, Juliana Young Koo, and sisters Genevieve “Gene” Young ’48 and Shirley Young ’51.

Her resourceful mother, whose mantra was “think positive,” settled in New York and got a job as a protocol officer at the United Nations. A friend told her about Abbot Academy, which would become a family tradition for all three Youngs, each attending on a full scholarship.

Their childhood was marked by loss and uncertainty, and Abbot helped them find new beginnings, making the sisters realize they could do far more than they ever thought possible.

Those were different times. But Frankie’s commitment and love for Abbot grew from them. The friendships she formed here, and what that meant to her, stayed with her for the rest of her life.

”Frankie Young arrived in the fall of 1953. During her four years at Abbot, she served as a chapel and corridor proctor, class officer, member of the dance group, a Fidelio singer, and a varsity soccer player.

“It was the American Dream,” explains Oscar Tang ’56, who met his future wife at a party in New York, where he discovered she was an Abbot student. He was attending PA, just up the hill.

Tang was 11 when he was sent to America in 1949, at the end of China’s civil war when Communists took Shanghai.

He recalls that Abbot, for Frankie, “was a hospitable place that provided a safe space to grow and experience the joys of an extended family, who were whole-heartedly dedicated to teaching how to gather the strength needed to be successful.”

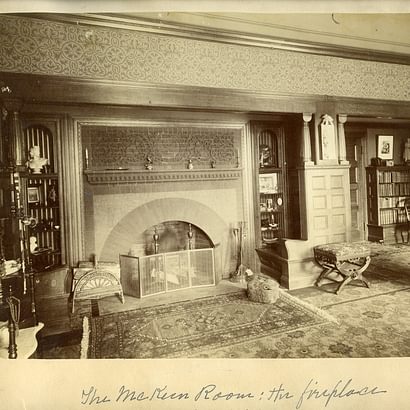

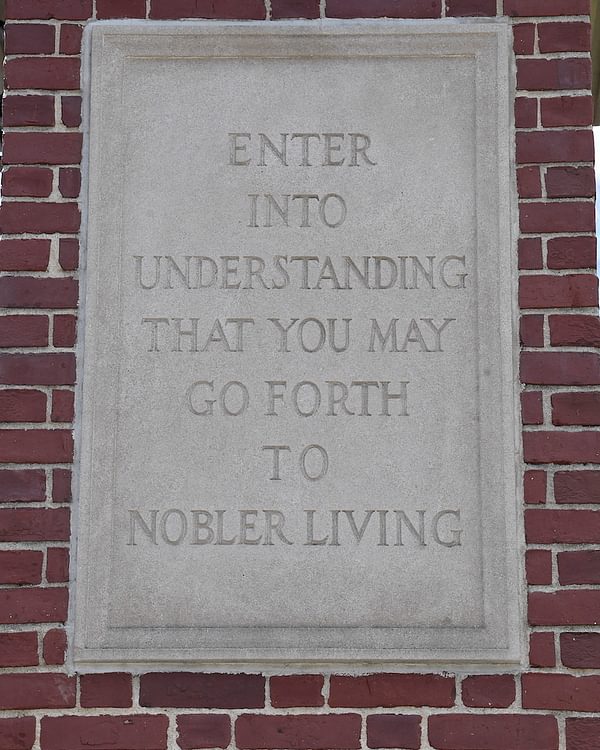

During that first year, the view from Young’s School Street bedroom overlooked the Merrill Gate, with its iconic brick pillars and arched iron grillwork. Beyond the gate, she could clearly see Draper Hall. The large and looming Romanesque-style building housed dormitory suites, the principal’s suite, dining rooms, a kitchen, a library, a reading room, art studios, 11 music rooms, and parlors for entertaining. It was in one of those grand parlors that Frankie and Oscar spent many an “Abbot Calling Hour” getting to know one another under the watchful eye of a chaperone.

“Those were different times,” laughs Tang. “But Frankie’s commitment and love for Abbot grew from them. The friendships she formed here, and what that meant to her, stayed with her for the rest of her life.”

Never Underestimate an Abbot Alumna

By the early 1970s, Abbot and PA were cross-enrolling students, opening up an extraordinarily varied academic program to both schools.

“I enjoyed the freedom and the double standard that worked in my favor,” writes one young woman in a 1971 questionnaire issued to Abbot students enrolled in coordinated classes.

“I felt very fortunate to be living in the loose, happy, responsive Abbot environment and to take classes at both places,” writes another.

But when students returned to Abbot for the 1972–1973 school year, they were surprised to learn the two schools would become one in June 1973. The news hit many hard.

For Abbot students, the sense of place is like no other. Barbara Timken ’66, an architectural historian, preservationist, and PA charter trustee from 1988 to 2004, recalls the school’s physical campus as the thing that first drew her in.

“It had that circle in the center, connecting everything,” she says. “There was a strong sense of identity. I just had a good feeling there.”

Although Abbot was founded in the 1800s by powerful men—reverends, deacons, and bank officials—who enforced morals and ran the town, the true forces behind the success of Abbot were Andover’s women, such as the school’s namesake Sarah Abbot, who, at the time, could not vote, own property, or enter many professions.

Perhaps they hoped simply to improve women’s station in society. Or, just maybe, the dream was far bigger. For 145 years, women would hold the key to Abbot’s progress, which is why the merger, for many, felt more like a setback.

“There was a lot of resentment,” Timken explains. “Other private schools going coed at the time were joining names, like Choate Rosemary Hall and the Loomis Chaffee School. A lot of my classmates felt like our history was being diminished, even erased.”

Pigeons were flying in and out of holes in the roof. We were devastated to see Abbot like this.

”Frankie Young—now Frankie Young Tang after marrying Oscar in 1960—had graduated from Skidmore College, where she studied textile design, and was well on her way to becoming a dedicated philanthropist in the field of education.

“Frankie took an opposite tact, “Tang says. “She strongly supported the merger and believed in the two schools’ future as one.”

A woman of determination and sprit, Young Tang partnered with Carol Hardin Kimball ’53 (PA’s first woman charter trustee) and wrote letters to every Abbot alumna to help ease fears that their alma mater would be forgotten.

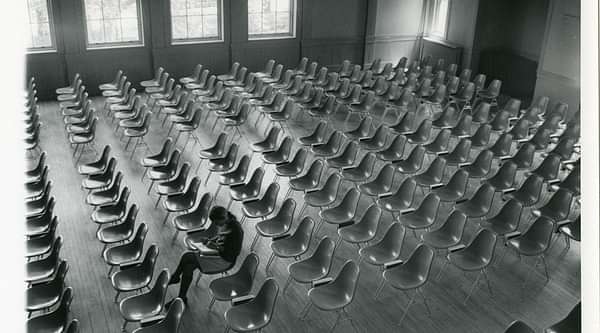

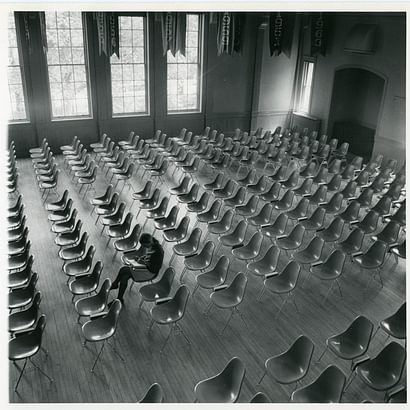

Yet after the merger, the Abbot campus grew visible scars from neglect. The once majestic Draper Hall stood empty and untended for 20 years.

Returning for their 15th Reunion in 1983, Abbot’s Class of 1968 took a long look around and felt their hearts sink. Weeds and overgrown grass pushed through cracks in the Sacred Circle’s walkway. Some windows in Draper Hall were boarded up, others had broken panes of glass.

“Pigeons were flying in and out of holes in the roof,” Finbury recalls. “We were devastated to see Abbot like this. While talking about how something had to be done, I was asked if I could help.”

Finbury happened to be a partner at Rufus Choate Associates, a historical preservation consulting firm that specialized in redeveloping significant buildings.

“The time is now,” thought Finbury. And seemingly overnight, she became the leader and fierce advocate of a preservation campaign that brought together the spirit of Abbot alumnae, the trustees of Phillips Academy, and the townspeople of Andover.

“Without Lanie Finbury,” says Neil Cullen, the chief financial officer of Phillips Academy from 1986 to 2004, “who knows if we’d have this story to tell. She inspired the conversation.”

The Center Holds

An immense presence designed by renowned American architects McKim, Mead and White of New York, Draper Hall had become a spectacle of majestic and tragic splendor.

Finbury arranged to tour the inside. Years of water damage and the repercussions of resident squirrels and pigeons made the building uninhabitable for humans, except for one glaring oddity—the Phillips Academy daycare center was operating out of the dilapidated building’s basement.

“One of the most important historical elements to understand when trying to make sense out of all of this is the tumultuous state of the country’s economy and the stock market in the 1970s,” explains Cullen, whose mountain of copious notes detailing efforts to preserve the Abbot campus reside in the Andover Archives.

Two economic recessions in the 1970s resulted in record unemployment and inflation. The stock market crashed, and both Abbot and PA were reeling from the financial squeeze—one of the factors that propelled the merger.

“As you can imagine, one of the PA’s primary resources, its endowment, was not performing well and over that decade was flat to negative,” Cullen says. “What could have been a lifeline for building and maintenance projects was unavailable.”

When the schools combined in 1973, the Northeast Document Conservation Center began paying rent to PA for the use of Abbot Hall as office space. They would be tenants for 20 years.

Some Abbot properties along and surrounding School Street that served as faculty and student housing were sold. Proposals that would have required the demolition of Abbot’s flagship buildings came and went because of a lack of interest among developers in an unstable market.

Lanie opened up the trustees’ eyes to seeing that these buildings could have a future.

”Finbury got busy working up a preservation plan that incorporated the history of the buildings and how to retain their look and character while providing an appropriate use of the space for the Academy. Beyond that, she proposed a detailed financial plan to make it happen, including federal tax incentives available to developers of historic sites. The Abbot campus, Finbury notes, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Abbot’s historical significance fueled the preservation mission. McKim, Mead and White of New York—whose notable works include the original Pennsylvania Railroad Station, The Brooklyn Museum, and The Boston Public Library—had designed both the Merrill Gate and Draper Hall.

“Lanie opened up the trustees’ eyes to seeing that these buildings could have a future,” Timken says. “Before that, I think it was hard to imagine that they could in fact be rich resources again—spiritually and financially.”

Welcome plaque on the right side Merrill Gate pillar. Photo by Gil Talbot.

Welcome plaque on the right side Merrill Gate pillar. Photo by Gil Talbot.

Phillips Academy, viewing Abbot from a new perspective, supported Finbury’s proposal and hired her firm to oversee restoration of the Abbot campus. McKeen Hall was first.

An Abbot Preservation Task Force was formed that included key figures who would help take up the cause with fervor. Young Tang took the restoration project to heart. During the mid-1980s, she made a donation to support the Abbot campus feasibility study, which was vital in keeping trustees focused on the issue.

Timken, a founding member of

the Academy’s design review committee, brought her expertise on a range of

historic preservation projects, including Graves Hall and the Oliver Wendell

Holmes Library in the 1980s. Many other dedicated and visionary alumnae/i

rolled up their sleeves on the reclamation and adaptive reuse of the Abbot

campus, which took more than a decade to see through.

There were wins and losses. In addition to managing renovations at McKeen, Finbury also became the de facto public relations director in the effort to save Draper Hall, which required a successful Town Meeting vote to allow a variation in zoning provisions for multifamily residences inside the building.

To help educate the community, Finbury commissioned hundreds of blue “Save Abbot” pins, held more than 50 public meetings and presentations, offered free doughnuts at weekend meet-and-greets in the lobby of a local bank—often with her toddler in tow—and went door to door to answer questions and promote the cause.

Following months of campaigning, a 1988 Andover Town Meeting—that included an impassioned speech by PA Head of School Donald McNemar on the responsibility of stewardship—drew the necessary two-thirds majority vote needed to permit the desired development in Draper Hall. While the initial plan was to accommodate rental apartments, the Academy shifted its focus to retaining full control of Abbot’s buildings, and the approved zoning changes eventually paved the way for multifamily faculty housing in Draper.

A jubilant Young Tang sent an oversized bundle of Abbot-blue helium balloons to George Washington Hall in celebration of the hard-fought victory.

Sacrifices were made, adds Timken, recalling a trustee vote to demolish Draper’s wings, including the south wing that once housed the dining hall where generations of Abbot students enjoyed fellowship and learned the art of good conversation.

“It was bittersweet,” says Timken, who voted to preserve the entire building. “But the great delight is that so much was saved in the end.”

Abbot Reimagined and Reborn

Out of Abbot’s neglected years emerged a vision of education for the 21st century: The trailblazing Brace Center for Gender Studies, the acclaimed Edward E. Elson Artist-in-Residence program, and the legacy of the Abbot Academy Fund, which has invested in innovative and exploratory approaches to learning since 1973. And it was the resourcefulness and wonderous optimism of Abbot alumnae that kept the school’s mission alive—and secured its future.

The core Abbot Committee, says Cullen, was never short on passion for the mission.

“Sure, there were many debates and controversies over the years,” he says. “That is to be expected in a project that is felt in the hearts as much as it is in the heads of those involved. But there was also great joy in the common goal, and part of that fun is the people you get to interact with—all were there to make something good happen.”

Young Tang had fully immersed herself in the preservation effort. She never did know how to do anything halfway. Call it an Abbot trademark. Between writing letters to keep Abbot alumnae in the loop and frequently traveling from New York to Andover to attend meetings and update trustees—including one unforgettable flight with Timken during a thunderstorm—for Young Tang, the work to breathe new life into the buildings she spent her formative years studying inside and out was an act of love that deeply touched classmates and colleagues alike.

I became a cluster dean 15 years after coeducation. And still, there was a sense that Abbot was special. It was different. There were students who purposefully and thoughtfully chose to be in Abbot Cluster because the legacy mattered to them.

”“Frankie was a force,” Timken says, “always bringing good energy and laughter wherever she went. She was, in many ways, the glue that held us together during tough times.”

Oscar Tang remembers the many stories his wife brought home about the project over the years. The artist inside her seemed to follow the lines of progress like climbing a grand staircase—leading to new perspectives from each change in elevation.

“Preserving Abbot was a larger issue than her own love of the place,” Tang says. “Good institutions must face forward and look ahead. Frankie believed the merger was the right thing to do, and part of that belief was that she had faith in the fact that Andover was first and foremost a place of inclusion. She believed her fellow alumnae would be included in Andover’s future; that Abbot’s legacy would be included in the legacy of Andover and that the preservation of the Abbot space was an integral part of the process of inclusion.”

As Andover has taught finis origine pendet, the end does indeed depend on the beginning.

Rebecca Sykes, former associate head of school and namesake of the Sykes Wellness Center, arrived at Andover with her husband in 1973, the year of the merger. She was a cluster dean from 1988 to 1993 when excitement about new student social spaces in McKeen and faculty housing in Draper was electric.

“I became cluster dean 15 years after coeducation,” Sykes says. “And still, there was a sense that Abbot was special. It was different. There were students who purposefully and thoughtfully chose to be in Abbot Cluster because the legacy mattered to them.”

The echoes of ambitious women from more than a century past continued to impact advancement in education. Sykes was part of a trailblazing group that defined the framework for the Brace Center for Gender Studies, the only center of its kind at a secondary school offering opportunities for students and faculty to research all areas of gender equity and intersectionality. Located in Abbot Hall, the center opened in 1996 and was funded by and named after Abbot legend Donna Brace Ogilvie ’30.

“To everything there is a season,” Sykes said. “And to see the season for some of the things we cared so deeply about come into bloom—especially supporting kids with dignity and respect for all, and on the Abbot campus—was rewarding. Having the Abbot name persist, not only in the minds of students but also our successor faculty colleagues and administrative colleagues, is affirming. It’s hard not to take personal pride in that.”

In 1991, Finbury was presented with the Massachusetts Historical Commission Preservation Award for her work in rehabilitating McKeen Hall.

“Every community has a story to tell,” says Finbury, whose mother Marion Finbury, director of college counseling at Abbot and PA for 23 years, was laid to rest in Chapel Cemetery at Phillips Academy in 2015. “I think the more respectful we are in understanding the story and all its chapters makes for a stronger future.”

After McKeen was renovated, the heart of Abbot broke again when Young Tang died in 1992 after a courageous battle with cancer.

Tang, a successful financier, knew exactly how he wanted to honor his beloved. He returned to Andover soon after her death to walk through Draper Hall. Finbury accompanied him.

Part of the roof had fallen away and its temporary cover had blown off during a storm. Water was coming down the walls and through the floor.

“I looked and wept, because it seemed that this shell of a once beautiful structure was a perfect mirror of the total despair that was in my heart at that time,” says Tang. “I was not a preservationist. What drove me was that it was important to Frankie. Our lives were intertwined by these two schools, and this was a gesture to bring Abbot alumnae back into the Andover family and keep their legacy alive.”

Tang made a generous gift of $5 million to breathe life back into Draper and restore the Sacred Circle. He would go on to serve as charter trustee from 1995 to 2012 and become board president.

In 1997, the Andover community turned out for a rededication ceremony to honor Young Tang’s memory and the renovated Abbot campus. There is a Frankie Young Tang memorial bench in front of Draper Hall and a small garden at the back of the building near the Maple Walk offering vantage points to pause, rest, and perhaps reflect on the history—and future—of Abbot.

“It’s lovely to think this campus will stand the test of time, allowing students to see just how buildings can be reinvented, reborn, and repurposed,” Timken says. “If you really look up close at a building and study the place, it can open up all kinds of opportunities.”