April 20, 2023

Making waves

Two alums find community and a life less ordinary in an unconventional sportby Jia H. Jung ’00

I had known Phil White for years, but it wasn’t until the fall of 2021 that we talked about something other than swimming—and made an interesting discovery.

I pulled up to his log cabin overlooking Lake Memphremagog, nearly 32 miles of water stretching over the Canadian border and fabled to shelter Memphre, a massive cryptid dwelling at the depths of 350 feet.

Nestled in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, Phil’s home, known as “the Clubhous,” is also the center of operations for a year-round program of athletic events that Phil began directing in 2007. His annual open water swims are responsible for transforming Newport, a city of 4,440 residents, into a pilgrimage site for thousands of athletes from all over the world.

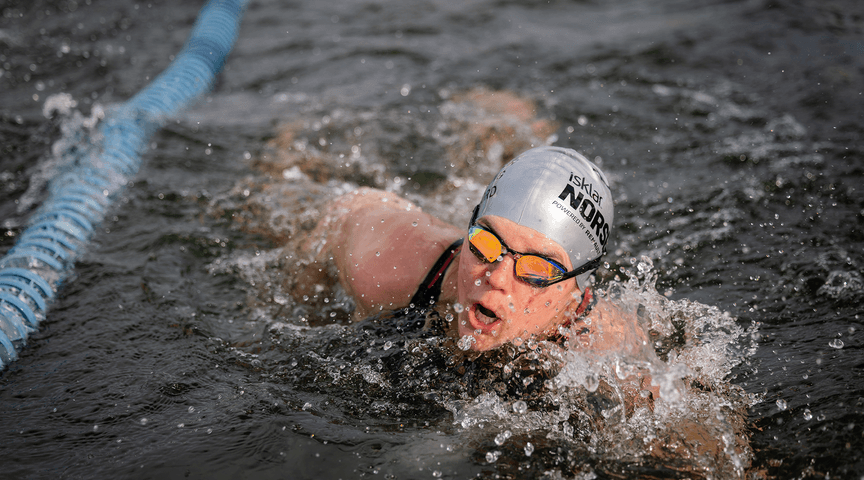

Open water swimming attracts people in search of the mental, physical, and spiritual benefits that come with immersion in lakes, rivers, and oceans. People like Sarah Thomas, famous for crossing the English Channel four times, and Ranie Pearce ’79, who started swimming at age 45—and has since evaded a persistent shark in Hawaii’s Kaiwi Channel and completed mile swims in water below 41 degrees—have journeyed to experience Phil’s array of open water challenges.

I was visiting the Clubhous to celebrate a successful 28.5-mile swim around Manhattan Island—and my 40th birthday. Phil looked up from a table laden with walkie talkies and mounds of paper. His white beard, which he began growing during the 2020 presidential election, hid his expression. He was busy, but I convinced him to take a break.

On our way to a diner, he remarked that he didn’t even know where I’d grown up.

“Andover, a little town northwest of Boston,” I told him.

“Oh yeah? I…went there,” he said.

“What, like you drove through?” I asked.

According to the World Open Water Swimming Association, there are around 12,000 people who have participated in 10K swims. Running into an Andover alum within a subculture shared by only 0.00015% of the human race felt outrageous, but somehow unsurprising.

Phil White ’66

Phil White ’66

Phil was born in 1948, with Princeton alumni on both sides of his family. His father, a World War II veteran, owned and operated a small paint store in New York’s Hudson Valley. Raised in a middle-class family, Phil attended the progressive Poughkeepsie Day School, where folk musician, social activist, and future Hudson River conservationist Pete Seeger played for the kids in 1961. The performance inspired Phil with concepts of anti-establishmentarianism and universal disarmament.

One year later, Phil was admitted to the Class of 1966 at Phillips Academy. Five-foot-four and weighing around 98 pounds, he moved into Williams Hall. In the all-boys school, he had to elbow his way into a spot by a window to catch a glimpse of the Abbot Academy girls practicing field hockey.

At Commons, Phil could always find someone to debate with about the peace signs and Sane Nuclear Policy buttons he wore. “There were a lot of super preppy kids but also a lot of odd ducks who were very bright,” he remembers. His fellow students included a prince from Siam and a boarder from Cuba who raised parakeets in his dorm room.

Phil received a 76 on his first English assignment but went on to make high honor roll, win an essay contest, and become a representative for Johnson Hall, where he lived lower year as a devout disciple of Taoism and Jack Kerouac.

Upper year, he moved into the newly erected Stimson House. His house counselor, Josh Miner, had recently established Outward Bound USA and the Search and Rescue program at Andover. Intramural opportunities made a lasting impression on Phil, who was no varsity athlete but enjoyed downhill skiing and could swim two lengths of a pool without taking a breath.

Phil studied Russian, ceramics, stage set construction, and acting his final two years. He applied photography skills garnered from his senior photo project to forge fake IDs from draft cards, which he sold to fellow students. Along with a childhood friend, Phil spent school breaks in New York City’s West Village, watching jazz visionary Sun Ra, meeting folk legend Arlo Guthrie, and reading beat writers who took roads less traveled.

At some point, Mr. Miner reassured Phil’s parents: “Phil is just going to have to make his share of mistakes, but he’ll be all right.”

The Phillips Academy I entered in 1996 was far different: coed, deliberately diverse, and with buildings retrofitted to satisfy the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act. The only area where I felt excluded was compulsory athletics. Unlike Phil, I didn’t take advantage of intramurals, humiliating myself instead in field hockey and lacrosse.

Music was my sport and salvation. Playing got me through my father’s death during my upper year and the loss of our class president and symphony oboist Zach Tripp to his on-campus suicide before senior spring. Prior to graduation, I performed a piano concerto. It was the most significant thing I did at Andover; I still talk about it the way a former quarterback reminisces about getting carried off the field after a big win.

In the fall of 2000, I was the only person in my class to matriculate to the University of California, Berkeley. The college is known for grooming Olympic swimmers—multi-medalists Natalie Coughlin and Anthony Ervin were both in school with me. But so firmly ingrained was my non-athlete identity that I visited the elite outdoor aquatic facilities mostly to deepen my tan.

A rower friend, however, began dragging me with her to the campus gym. Weeks later, I jumped into the marble-lined, rooftop Hearst Pool to cool off. I swam one lap and then another and another. Aerobic machines had extended my endurance—I felt like I could swim forever.

There’s a life form that comes out of Andover. The force to excel that comes from that school—I can’t escape it. I can’t deny it. It was the spawning ground of moving forward.

”After PA, Phil attended the University of Chicago briefly before dropping out and moving to New York City’s Lower East Side. A series of odd jobs followed—transporting marijuana from San Francisco to the East Coast, carpentry, and driving horse carriages in Central Park.

Phil was drafted at the apex of the Vietnam War in 1968. When a military evaluation resulted in a deferral from deployment, he enrolled in general studies at Columbia University. After graduating with a major in political science, he entered Georgetown Law School in 1975 to become an environmental mediator. However, while working at a civil litigation clinic, Phil helped obtain a court order in favor of a woman whose landlord had illegally locked her out of her apartment in a gentrifying area of Capitol Hill. The exhilaration of the fight turned his focus toward trial law.

Phil moved to Vermont in 1978 and served as a state’s attorney for a decade before entering private practice as a civil trial litigator. Among his most notable cases, Phil prosecuted sex abusers and helped expand victims’ rights, services, and compensation. In the early 1990s, he mobilized and represented survivors of child abuse at the notorious St. Joseph’s Orphanage in Burlington.

By the millennium, Phil had purchased the Clubhous as a year-round camp and moved to the lake fulltime while his daughter attended college in Quebec.

I had always loved the water, but it wasn’t until I moved to New York City in 2010 that I became a swimmer.

By this time I had completed a couple of one-mile swims, amazed to be capable of anything athletic. The colossal outdoor city pools held adult lap-swimming sessions before and after office hours in the summer. It was easy to break the one-mile barrier in these urban bodies of water. All worries, uncertainties, and frustrations washed away upon submersion; every joy was magnified.

That first summer I decided to try something different and registered for a three-mile race off Coney Island. On the big day, I headed to the subway at 4 a.m. and rode the F-train to the boardwalk. I ran into the slate-colored water with people I didn’t know yet. A thunder of instinctive terror can hit the chest when the ocean floor drops away into darkness. The fear becomes a familiar gate to pass through before seeing the world with fresh eyes from the water.

With the sun on my back and the cool Atlantic underneath, my thoughts vacillated between the petty and the profound before allowing me to merely exist, like plankton or a transcendent being. Tenderized, I emerged onto the warm sand around 10 a.m. and staggered toward the refreshments. Chugging a local craft beer, I thought, “I could do a whole lot more of this.”

My entry into open water swimming paralleled Phil’s ascent as an athletic director. We were both part of the sport’s global wave of popularity that was set into motion by the debut of the 10K swim in the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the rise of social media, which brought virality to fitness.

Phil loved Vermont. Deeply involved in the community, he threw himself into trying to save an indoor sports facility that was in danger of closing. He organized bike rides, runs, and swims to raise money. His efforts to save the center failed, but he had tapped into a paradise of outdoor recreation that was bringing people together.

On August 28, 2013, Phil incorporated the Kingdom Games, which, over the years, has grown to offer more than 50 days of running, biking, open water swimming, and winter swimming events each year in northeastern Vermont and the Eastern Townships of Quebec. Instead of offering cash prizes to winners, Phil distributes proceeds from events to local businesses and cancer-battling organizations.

I started hearing swimmers mention Phil’s name as my own swim distances increased: Remember when Phil said this? Remember when Phil did that? Remember when Phil grounded his boat on the rocks? Remember when Phil sank his truck through the ice?

The first time I jumped into Lake Memphremagog to swim to Canada in 2019, I formed my own special affection for Phil. I stopped an hour short of the 11.5-hour cutoff to give my kayaker a break when I knew I could not finish in time. When I returned to the dock with the other stragglers, Phil was there, jumping and waving, even after the last volunteers had gone home.

It’s this level of support and care that earned Phil the 2019–2020 Service to Marathon Swimming Award. During the pandemic, he managed to maintain and grow the open water swim community with COVID-compliant gatherings and a virtual winter swimming festival. And in late 2022, Phil unveiled Project Welcome, a fund to waive swim expenses for underrepresented athletes. He had long observed the sport to be “way too white” and wanted to change that.

I started hearing swimmers mention Phil’s name as my own swim distances increased: Remember when Phil said this? Remember when Phil did that? Remember when Phil grounded his boat on the rocks? Remember when Phil sank his truck through the ice?

”On a sunny, cold day this past February, a trio of Carhartt-clad “ice boys” plunged their chainsaws into the frozen surface of Lake Memphremagog, liberating a pool-sized rectangle of black water for the 2023 winter swimming festival.

A record 155 competitors showed up. A semicircle of flags at the edge of the pool represented countries from around the world, honoring the homelands of everyone who had ever participated in the event.

Phil’s beard—which added insulation on the 11-degree day—was even longer now. (He vows not to shave until every Russian soldier exits Ukraine.)

At 74 years young, Phil stood at the ice’s edge shouting prompts for the safety team to assume their positions before contestants sprinted down the lanes. At poolside, towels trampled by wet feet froze stiff and resembled snow sleds, providing photo ops for grinning swimmers.

The eclectic crowd included people who had attended the event every year since its inception as well as newbies, cancer survivors, a 77-year-old woman, and the fest’s first transgender participant.

Watching swimmers gasp and thrash through icy water to reach an inexplicable state of bliss, it struck me that Phil and I had something else besides PA and the lure of open water swimming in common: a wish to never be ordinary.

“There’s a life form that comes out of Andover,” Phil says. “The force to excel that comes from that school—I can’t escape it. I can’t deny it. It was the spawning ground of moving forward.”

The drive to keep moving finally led Phil to his people, a community that feels welcome in this safe space he built for wild adventures.

My extraordinary friend cites how Herman Hesse’s Siddartha finds peace as a ferryman, shuttling travelers across the river that separates the regular world from enlightenment.

“My quiet presence in this phase of my life is not dissimilar,” he muses.

Thanks to Phil, we are not alone.

Jia H. Jung was the 2022 Li Center for Global Journalism Fellow at Honolulu Civil Beat, a position supported by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and the Institute for Nonprofit News. Her freelance work has been published in The Korea Times, Atlas/Gastro Obscura, SAVEUR, and Eastern Standard Times Media, with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Photos & video by Henry Marte