December 13, 2023

The Peabody, archaeology, and Native American justice

How Andover’s 122-year-old institute is taking a new approach to teaching by putting Indigenous voices front and centerby Rita Savard

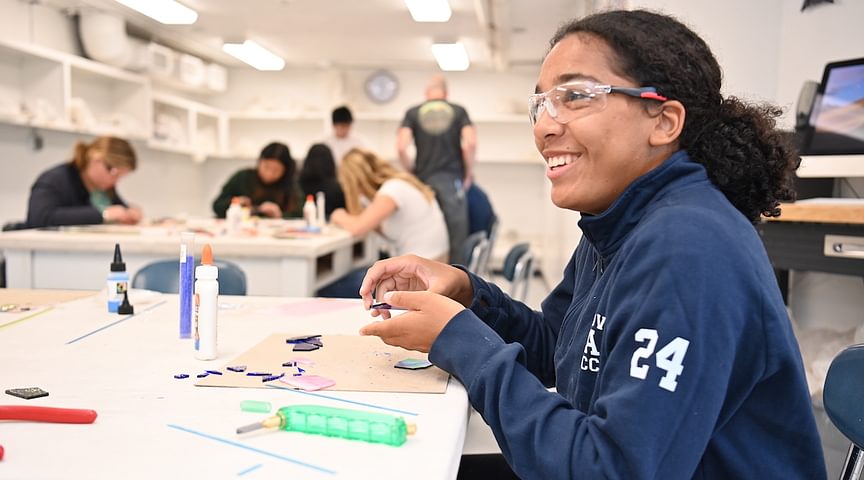

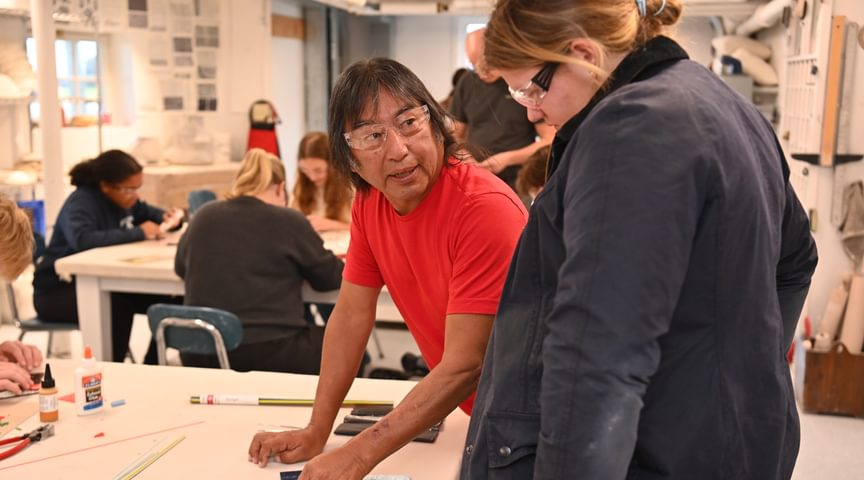

Standing over a long white table, Ramson Lomatewama reaches across an abstract collage of cut glass in different shapes, sizes, and colors.

The educator, artist, and poet explains that there is no word in his native Hopi language for art.

“We use the word for ‘children’ to define art,” Lomatewama says. “There is a part of you, the creator, in the creation. That extension of you—that connection—is never lost in what was made.”

The first and only Hopi glass blower, Lomatewama uses art as a bridge to link the past with the present. He shares his experience with students and faculty at the Robert S. Peabody Institute of Archaeology during a balmy week in October. Since its inception in 1901, the core of the Peabody’s mission has been to teach students. But today’s Peabody is not only taking a new approach to how archaeology is taught in the classroom, it is also helping correct history by putting Native and Indigenous peoples at the center of their own stories.

“Bringing in educators like Ramson to tell their personal stories is vital,” says Ryan Wheeler, director of the Peabody. “Native Americans are still here despite centuries of discrimination and oppression that included murder, forced relocation, and cultural assimilation. Their stories are very much present tense.”

Lomatewama’s journey from premed student to

becoming an educator to discovering his calling as an artist—has been a winding

road fraught with hurdles. Now 70, his childhood is marked by a long, dark

legacy of cultural cleansing in the United States, when the Native American boarding

school system was an entrenched, government-funded institution that separated

Native children from their families and cultures.

It’s no wonder the first lesson he teaches students about

working with glass as a medium isn’t actually learning about glass.

“It’s all about overcoming fear,” Lomatewama says. “As we learn more about what we’re capable of, we find a balance point.”

As the first Hopi artist to put glass blowing on the map, Lomatewama had to fight to take control of his narrative.

“Initially, showing my work at art markets was difficult because I took a nontraditional path,” he explains. “People would say, ‘That’s not Indian art,’ because they had formed a stereotype of what they thought Native art should look like. I had to validate myself to the art world, but I knew I had something rich. I found a way to express Hopi ideas and concepts through a totally nontraditional medium, and that is what I continue to do today.”

Phillips Academy is the only secondary school in the United States that can count an archaeology institute as part of its curriculum. For the modern-day Peabody, this presents a unique opportunity to bring long-term perspective to the human experience—an experience where Native stories are alive and illuminating.

Unearthing a Complex Cultural History

The ruins of Pecos Pueblo are about 28 miles southwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was here that an excavation from 1915 to 1929 by Alfred V. Kidder, sponsored by the trustees of Phillips Academy, uncovered more than 2,000 human remains, thousands of funerary items, and a number of objects of cultural patrimony. Worn by time but preserved by the earth they were buried in, Kidder’s findings provided a key to unlocking Pecos’s past—and established a new scientific methodology in American archaeology.

Introducing the concept of seriation, Kidder helped develop a classification system to distinguish the different cultural periods of the region going back 2,000 years. Derived from geology, the basic concept is that the youngest material is found on the top, with each underlying layer representing an older deposit—making it possible to assign a relative date to materials removed from the various levels. Kidder’s approach was the first new, explicitly scientific archaeology in the Americas, explains Wheeler, and through his work the Peabody “became an exemplar of scientific archaeology in the Southwest.”

“Today, most of our knowledge of Pecos’s archaeology comes from A.V. Kidder’s excavations,” Wheeler says.

“That dig led to Kidder becoming known as a founder of American archaeology. His work changed the field of study, but that legacy is marred.” — Ryan Wheeler

Kidder, according to his own records, was not prepared for the discovery of so many burials. Still, he took all the ancestral remains he found, with no consideration of or discussion with descendent communities. While Kidder’s methodologies were common practice at the time, they stand in stark contrast to advances in practice since the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was signed into law by President George H.W. Bush ’42 in 1990.

A critical human rights law, NAGPRA required museums, institutions, and federal agencies to return Native remains, sacred items, and objects of cultural patrimony to the lineal descendants and Tribes they were taken from.

“NAGPRA held a promise,” says Marla Taylor, the Peabody’s curator of collections. “But more than 30 years after the law was passed, so much cultural property is still held up in museums and institutions across the country and around the world.”

Since the 1990s, Phillips Academy has built and nurtured ongoing friendships and educational partnerships with with the people of the Pueblo of Jemez in New Mexico. Pictured above are students who took part in the Peabody's Pecos Pathways program to learn about ancestral and contemporary Native communities.

Since the 1990s, Phillips Academy has built and nurtured ongoing friendships and educational partnerships with with the people of the Pueblo of Jemez in New Mexico. Pictured above are students who took part in the Peabody's Pecos Pathways program to learn about ancestral and contemporary Native communities.

At the Peabody, NAGPRA is ingrained in daily work. Wheeler and Taylor defer to Tribal nations’ knowledge of their customs, traditions, and histories when making repatriation decisions. Their network of community members—from the institute’s advisory board to long and close relationships with Native and Indigenous leaders—offers collaborative insight that informs stronger practices, including the completion of a major inventory project in 2021.

Since the 1990s, the Peabody has repatriated thousands of cultural items through NAGPRA. But for the first time in the institute’s 122-year history, all 600,000-plus items in the collection have been cataloged and are accessible through a searchable database.

Led by Taylor, the four-year project, which she refers to as a labor of love, has identified thousands more items potentially subject to repatriation. “These resources are critical to our educational mission,” Taylor says. “Starting with NAGPRA gives perspective and opens the door for conversations about control over cultural heritage.”

Establishing Connections to Tribes

For some, there was never a question about which way to go concerning NAGPRA. James Bradley was director of the Peabody in the 1990s when talks began with the people of the Pueblo of Jemez to return their ancestors and transfer ownership of cultural items, excavated by Kidder, from the Academy back to Jemez Pueblo and Pecos National Historic Park in New Mexico.

The long and difficult process took more than six years, but in May of 1999 the remains of 2,500 ancestors and thousands of associated funerary belongings were returned. Bradley, along with Leah Rosenmeier, the Peabody’s former director of external programs, education and repatriation coordinator, attended the burial ceremony with the Jemez and people from other Tribal nations. Around 200 Jemez Tribal members spent three days walking the 120-mile-journey from Jemez to Pecos Pueblo, retracing their ancestors’ steps.

Bradley penned an essay about the experience in the book Glory, Trouble, and Renaissance at the Robert S. Peabody Museum of Archaeology, edited by Wheeler and former Peabody director Malinda Stafford Blustain. During the ceremony’s presentations and acknowledgments, Bradley describes the bright blue sky darkening as clouds moved over western cliffs.

“Soon plumes of rain sweep down from the purple-black sky, turning portions of the intensely colored landscape into a gray scale of silhouettes,” Bradley writes. “Here, rain is a blessing that brings life to a beautiful but otherwise barren world…the Native people all notice and nod.”

The Pecos Repatriation of 1999 remains the largest physical repatriation to any federally recognized Native American Tribe in the United States due to NAGPRA. The return of Native remains is being closely documented by the nonprofit investigative news source ProPublica and can be tracked on their website.

Ongoing efforts aim to raise that number to 100 percent, Taylor adds.

Of the 617 institutions that reported holding Native remains, 104,539 ancestral remains—49 percent—have not been made available to Tribes.

Archaeologists, Wheeler adds, have an ethical responsibility to work alongside descendant communities to protect their cultural heritage from the forces of greed and unchecked cultural imperialism. But so does the public at large.

“Every time we talk about Native people in archaeology, we emphasize that these are people who are still here,” Wheeler says. “And that is not something that is typical in curricula anywhere.”

The Peabody ranks among the highest return rates in the nation, reported to have made 95 percent of its ancestral remains available. — ProPublica

Fertile Ground for Learning

Since the 1990s, an ongoing, active relationship between Jemez and the Peabody continues to impact student learning. From cultural exchange programs to Native and Indigenous guest speakers and teachers sharing their insights, primary sources provide new perspectives for students and faculty. Visiting the Jemez community through the Peabody’s Pecos Pathways program during his senior year, says Andrew Lyman ’09, was “transformative.”

“Being on the reservation was incredible,” Lyman says. “The Jemez have been there for hundreds of years and to be welcomed into their homes, to share their food, to hear them speak their language, join in their festivals, and be fully immersed in their culture—it was powerful. We were all friends by the end, and those friendships remain a valuable part of my life to this day.”

This fall, 14 years after Pecos Pathways, Lyman was reunited with longtime Jemez friend Jesirae Lucero, and the pair visited Andover. Their first stop: the Peabody.

“The Peabody opened my eyes to travel and experiencing new places and cultures,” Lyman says, adding that his next destination is Romania, a place the institute also put on his radar when he worked as a student volunteer. “I owe my lifelong passion for history and travel to my time there.”

Each year, Andover faculty see transformations like Lyman’s up close.

“For nearly 10 years now, the Peabody has funded a weeklong workshop for my students where they get to work closely with the Toya family, all ceramic artists, from Jemez Pueblo,” says art instructor Thayer Zaeder ’83, P’17.

“Those experiences are truly unique for young people and in many instances mark their first interaction and connection with Indigenous Americans. It enriches their worldview and strengthens their humanity.” — Thayer Zaeder

“Without the Peabody,” adds English instructor Sarah Driscoll, “students would not have the in-person conversations and discourse so vital to developing cultural competency.”

Living Archaeology

Inside Benner Hall, where students explore the art of glassmaking, Lomatewama tells the story of his own journey into a world of light and color. After taking a tour of the famous Corning Museum of Glass in New York during the late 1990s, Lomatewama remembers saying to a security guard, “I think I found my calling.”

Since then, he opened his own hot shop next to his house on the Hopi reservation in Arizona, built by hand through research and welding skills he learned in high school. Lomatewama teaches glass art for the Hopitutuqayki (Hopi School) and the Idylwild Arts Academy in Southern California, passing his passion on to a new generation.

“The strong point about coming from an older culture like Hopi is that it is very art oriented,” says Lomatewama. “You build your reality around your environment, around your community, around ceremonies and rituals. I came from a strong background, learning my cultural identity from the stories passed down by generations.”

For a very long time, non-Natives wrote as though Native American history was set in motion by the so-called “discovery” of the New World. In early historical works, explains Wheeler, Indigenous people are portrayed as supporting actors in the story of America.

“By writing Native peoples out of the past, this version of America’s story also denied them a present and a future,” Wheeler says. “Archaeology at the Peabody is multidisciplinary. It’s baked into courses that touch history, art, biology, chemistry, math, everything. Students engage with people, with items, with cultural differences, and...

“as we engage with difference, we open up a greater space for inclusivity.” — Ryan Wheeler

Marcelle Doheny’s classes widen the lens on the history of

Indigenous peoples, which includes teaching about The Dawes Act of 1887, that

regulated land rights on Tribal territories within the United States, NAGPRA,

and Indigenous Civil Rights. Archaeology at the Peabody plays an important role

in experiential learning for her students, presenting tangible ways to learn

about the past and present.

Students at the Peabody Institute of Archaeology practice close looking with Director Ryan Wheeler and engage with cultural items in meaningful and personal ways. Photo by Gil Talbot.

Students at the Peabody Institute of Archaeology practice close looking with Director Ryan Wheeler and engage with cultural items in meaningful and personal ways. Photo by Gil Talbot.

“It’s so valuable to have students learn to read objects,” Doheny says. “The archaeological record is central to a fuller understanding of history, and the Peabody’s collection forces kids to think outside the usual box of written evidence.”

Speaking truth to history is the future of American history, according to Wheeler and Taylor. And the Peabody is actively working toward a future where Native peoples and Tribal sovereignty are respected and supported—and where Native peoples shape, author, and control their own narrative.

“Letting Native and Indigenous peoples share their stories firsthand, and the stories their ancestors shared with them, is a powerful way to increase understanding of perceptions, places, histories, and issues we all value,” explains Taylor. “Just like we lean into our own family histories, descendants are the historians and persistence is forged from their stories.”

Change the Story, Change the Future

The Peabody’s work in recent years stretches far beyond Andover. Wheeler, Taylor, and their small but dedicated team are sharing their knowledge with other museums and academic institutions around the world. Nearly three years ago, Taylor co-founded the Indigenous Collections Care Working Group (ICC), composed of 20 Indigenous and non-Indigenous members who are creating an Indigenous Collections Care Guide—a how-to for helping re-educate and shift perceptions.

Historically, museums and academic institutions have acquired and amassed Indigenous cultural items for their own use and benefit with minimal consideration of descendent communities. The ICC was established to advocate for approaches that privilege Indigenous knowledge and center concepts of culturally appropriate care for items in museums. The guide, explains Taylor, will provide a framework to respect and recenter collections stewardship practices around the needs and knowledge of Native American community members.

“The Peabody has been at the forefront of repatriation from the very beginning, with the Pecos repatriation in 1999,” says Melanie O’Brien, manager of the National NAGPRA Program. “Most of all, through its leadership, the Peabody Institute has demonstrated the ability to listen to the needs of its Tribal partners and museum collaborators first."

“While the Peabody has made steady progress on its own collections, Ryan and Marla have facilitated exponentially more repatriations by being responsive and open to any options that assist with the overall goal of returning Native property back to the rightful owners.” — Melanie O’Brien, National NAGPRA Program

Laws alone are dry, adds Taylor. Humans experiencing joy over the outcome of the law has emotional impact. For some students the Peabody’s programs, which bring them closer to understanding the human impact, are life changing.

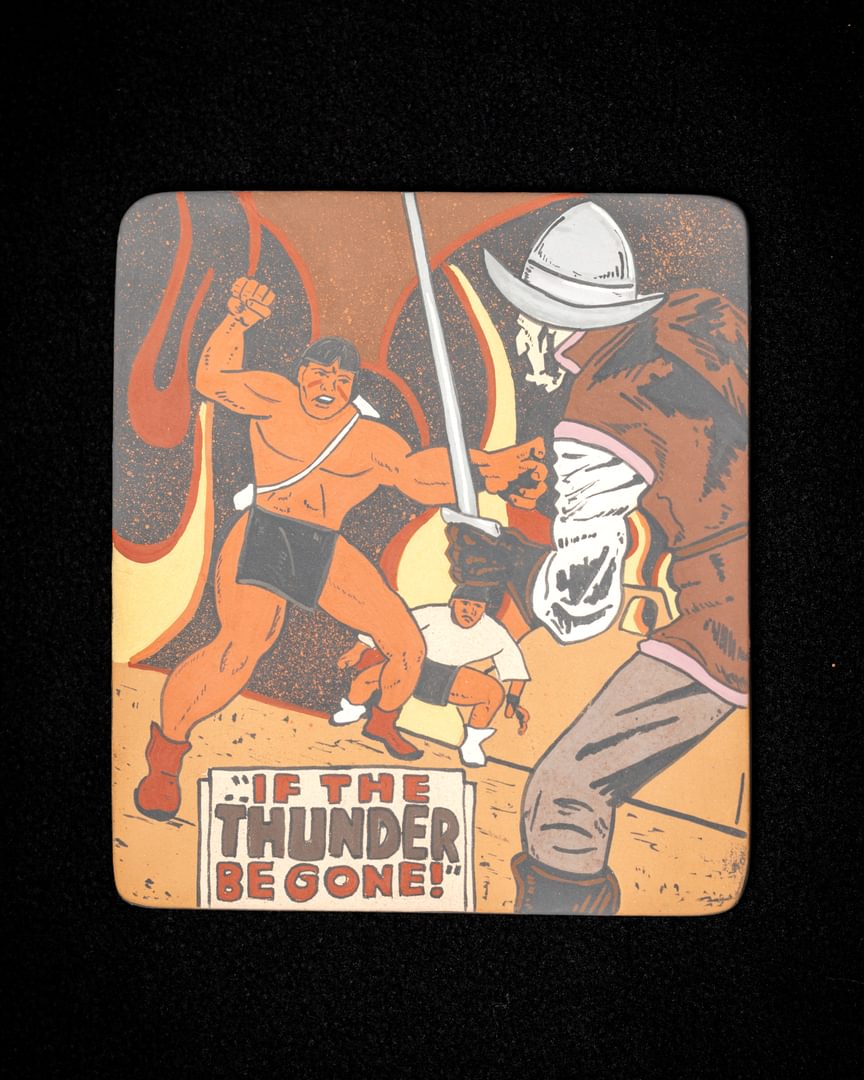

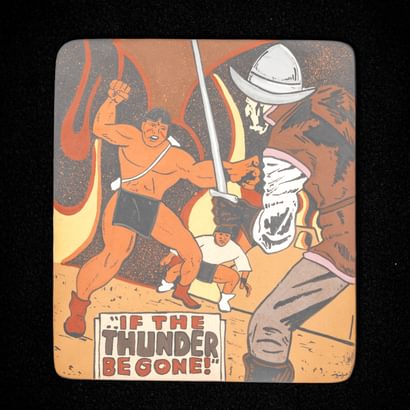

Collectively, explains Anthony Chung Yin Woo ’24, Native voices tell a singular story of Indigenous survival through more than 500 years of colonialism—one of the most extraordinary stories in human history.

Recalling a miniature scene in a dated diorama of Native American life, Woo was introduced to the significance of historical depictions and the ethics and responsibility of who is telling the story—and who is missing from it.

“Having hands-on access to the Peabody’s collection brought stories to life,” says Woo. “The experience inspired me to think more closely about engaging with local groups to learn more about the vernacular side of history, which is often omitted in the classroom. Taking the time to listen not only demonstrates care, but also helps us better understand the people in our communities.”

Discover more about the Peabody Institute of Archaeology at Andover.