February 06, 2024

Leveraging change

Before becoming a lifelong environmental rights advocate, Jerry Secundy ’59 helped desegregate Harvardby Joseph Kahn ’67

Each Thursday morning, Jerry Secundy joins a group of Harvard classmates on a Zoom call from his home in Pasadena, California. Topics for discussion vary from the personal to the global, usually centered around a guest speaker.

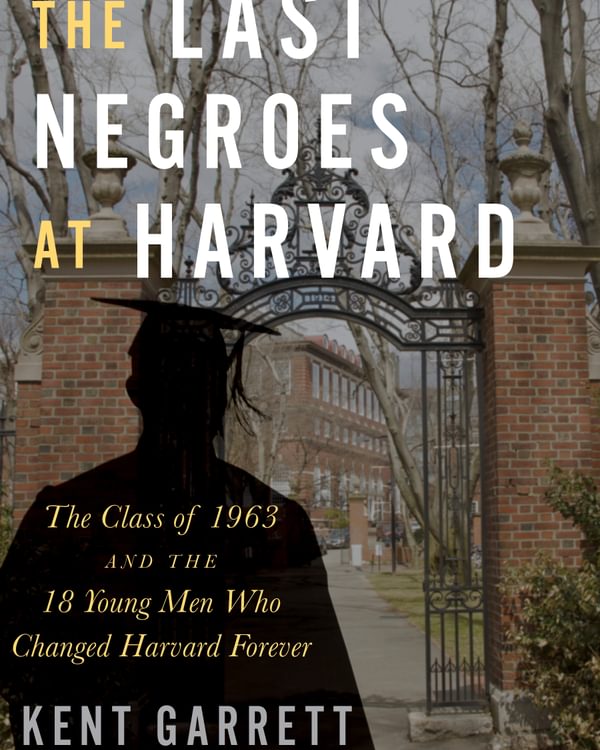

The group itself is historically noteworthy—several participants are among the 18 alumni profiled in the 2020 biography, The Last Negroes at Harvard—and Secundy is among its most accomplished members.

During a career spanning six decades of government service and private sector employment, Secundy has worked for a U.S. Justice Department office suing environmental polluters; various divisions of the Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO); the National Audubon Society and its California affiliate; and his state’s Water Resources Control Board and Council of Environmental and Economic Balance (CEEB), a trade association focused on air, water, and waste issues.

At 82, Secundy remains fully engaged, not only with protecting our natural resources but also with his lifelong passion for birdwatching, which grew out of an Andover biology class field trip. Yet even before PA and Harvard, he was navigating a world where racial identity and love of nature played outsized roles.

He grew up in a poor Black

section of Washington, D.C., the son of a Black mother and white Jewish father.

He received an early education in discrimination and what it meant to keep

people apart from one another based on how they looked.

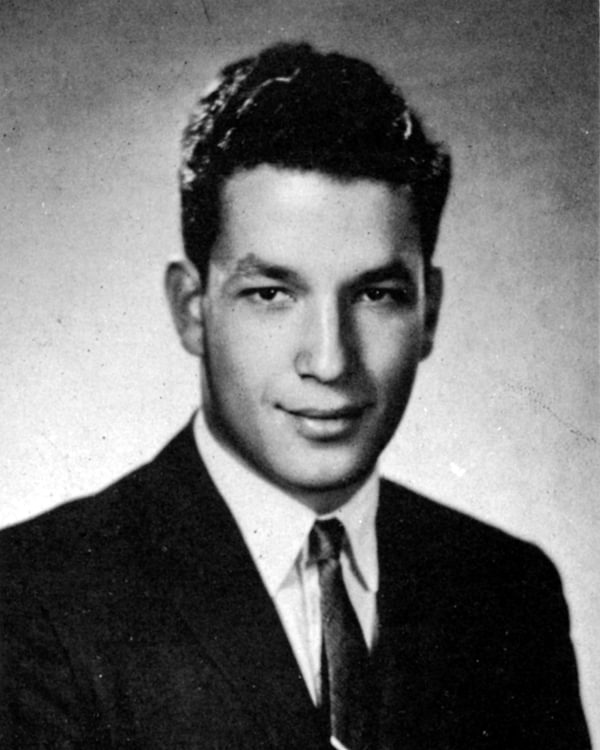

Jerry Secundy, Class of 1959

Jerry Secundy, Class of 1959

Summers were spent by the Chesapeake Bay at the only beach open to Black families. All other beaches were for whites only. There he spent many happy hours as a young boy catching crabs in a nearby lagoon. Even then, he found joy in nature.

“In retrospect, that started me on the road to becoming an environmentalist,” Secundy remembers. “It was a magical place for me.”

His early schooling was mediocre and occasionally fraught; while helping integrate a local junior high school, he and other Black students were greeted by ugly racist lawn signs. His parents were set on his getting a quality education, though, and after gaining acceptance to Andover he joined a class with just three other students of color.

“Andover was like being on a different planet,” Secundy recalls. “I struggled mightily at first, because I didn’t know how to study.”

He learned quickly and graduated near the top of his class. Nevertheless, he rarely felt fully assimilated and would introduce himself by announcing, “Hi. I’m Jerry, and I’m a Negro.” His intent, he says, was to let others immediately know “who I was and where I came from.”

Crediting PA with unlocking his academic potential, he also remembers mostly feeling like an outsider. Harvard, a bastion of white privilege in 1959, was not much different. Before his class came along, no more than a small handful of Black undergraduates had attended; there was no Black Studies curriculum nor a Black student organization. With the civil rights movement gaining momentum, though, the university was facing an internal push to diversify, a change that would accelerate as the ’60s marched onward.

The Last Negroes at Harvard is the compelling story of the Harvard Class of 1963, whose Black students fought to create their own identities on the cusp between integration and affirmative action.

The Last Negroes at Harvard is the compelling story of the Harvard Class of 1963, whose Black students fought to create their own identities on the cusp between integration and affirmative action.

The Last Negroes at Harvard is equal parts memoir, group biography, and history of a turbulent era as it chronicles 18 remarkable Black men admitted to Harvard’s class of 1963. The term Negro was used for the title because it was the identifying term used during the four years the Black students were there. However, by the time they had graduated, the standard term shifted, and they were calling themselves African Americans. Secundy and his classmates became game-changers: the “last Negroes” to pass through Harvard’s gates and part of the first wave of a revolution that would forever change other elite institutions.

“We broke that color barrier, and after that there was a deluge of Black students admitted to Harvard,” says Secundy, noting a highlight of his college experience was a one-on-one, hour-long meeting with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “It was a great deal of personal satisfaction to be part of this movement.”

After college came Columbia Law School, then two years with the Peace Corps in Peru before Secundy entered the workforce and turned his passion for environmental justice into various career opportunities.

The world was different then, he acknowledges.

“Climate change was not talked about that much,” he says. “What was talked about was water quality and air pollution and how we could make a positive impact.”

His work today as an environmental consultant reflects similar priorities. Yet he is realistic, too, about how quickly—or slowly—humans can adapt to the threats posed by climate change.

“No energy source is pure or pristine,” including electric vehicles, he asserts. “Nothing is free, either.” In California, he adds, “We’re trying to do the things that are the most cost-effective and easiest to achieve.”

A defining issue of our time, climate change comes up frequently during Secundy’s weekly Zoom calls as does the continued struggle for racial equality.

“Having understanding peers to lean on in good times and bad can be lifechanging,” he says. “We don’t all agree on everything, but it’s fascinating to hear what people have done and how they’ve survived all these years later.”